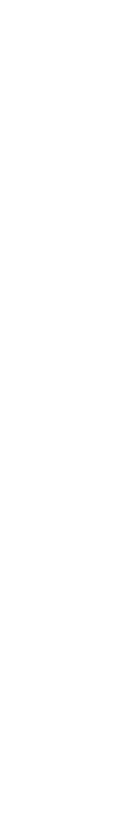

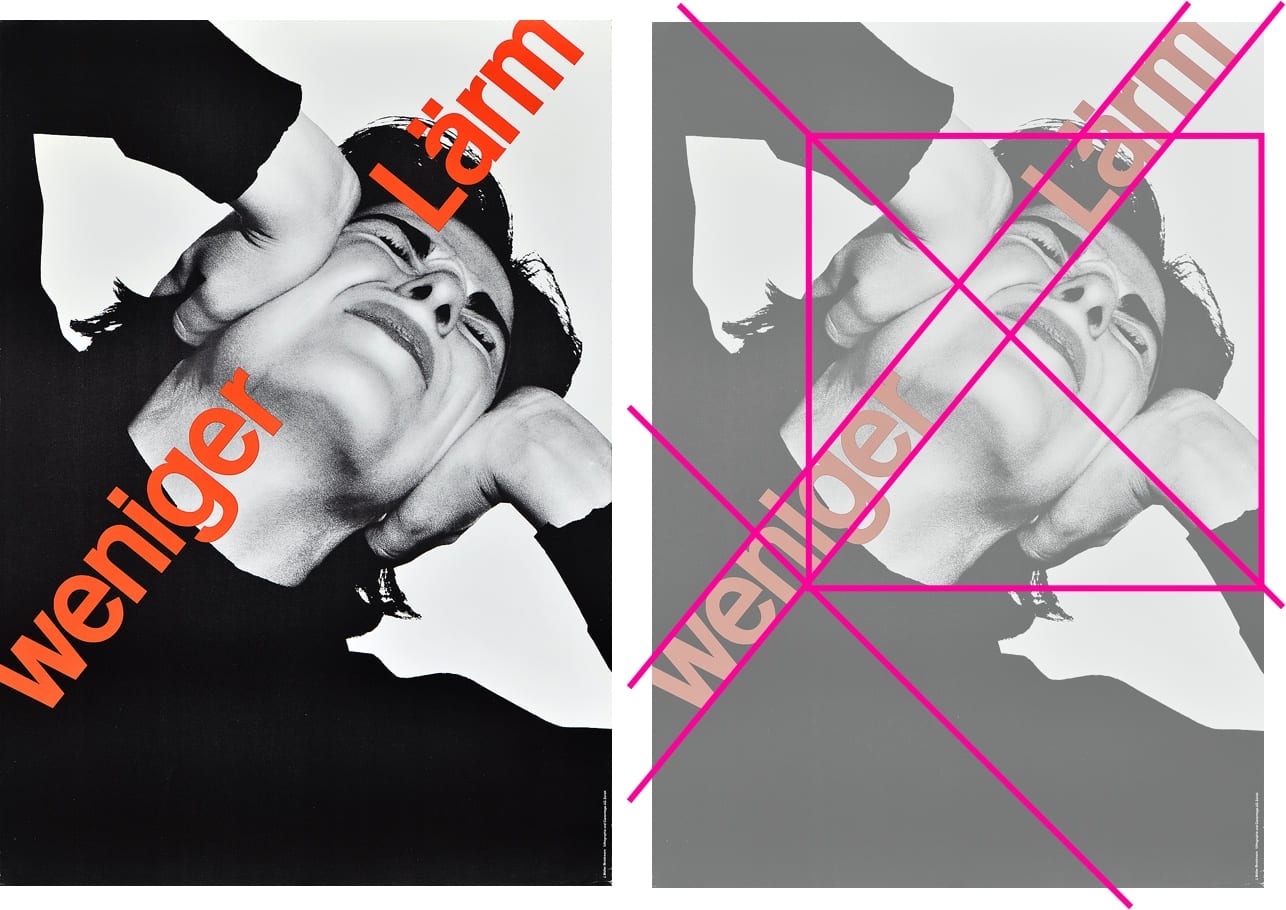

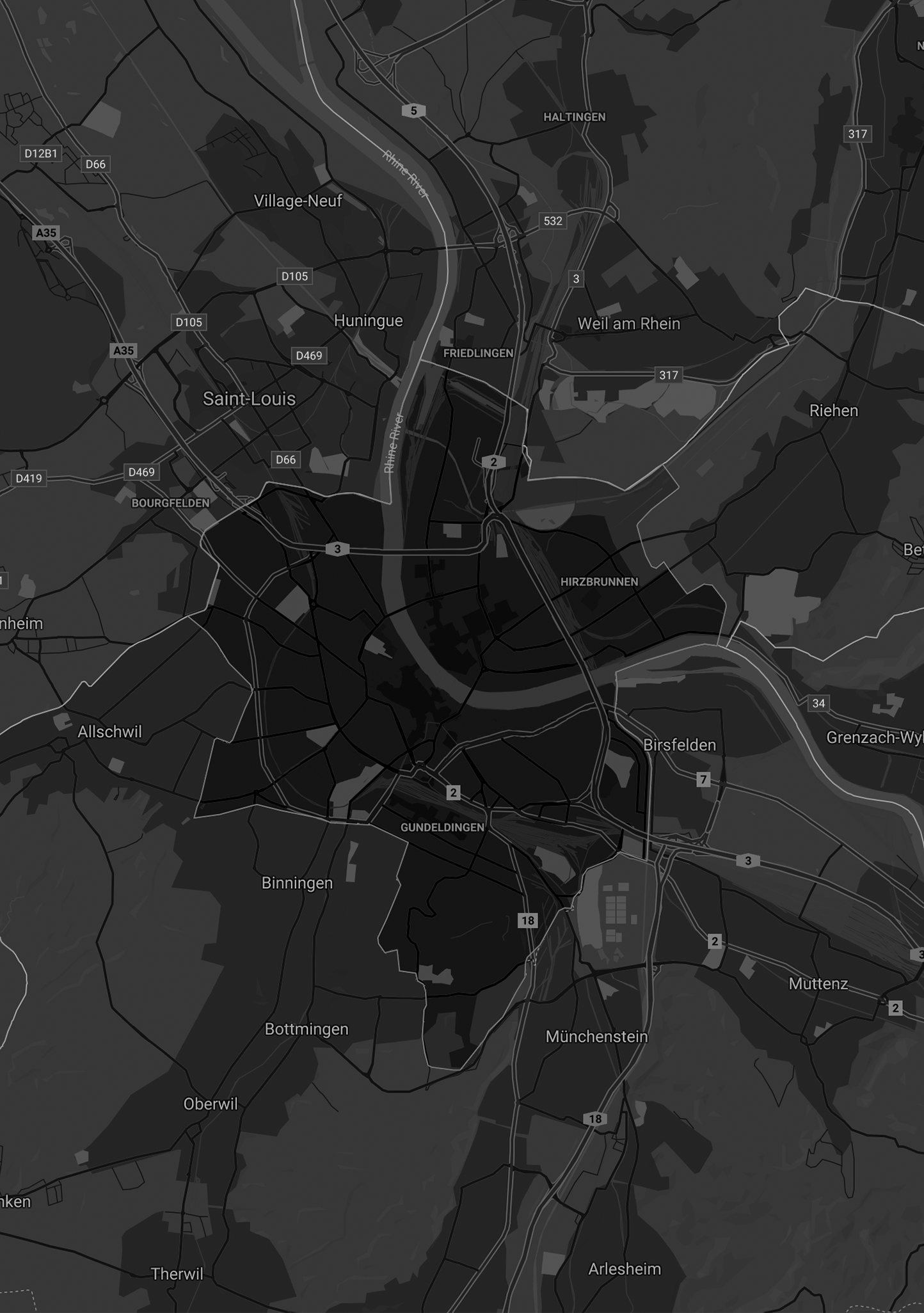

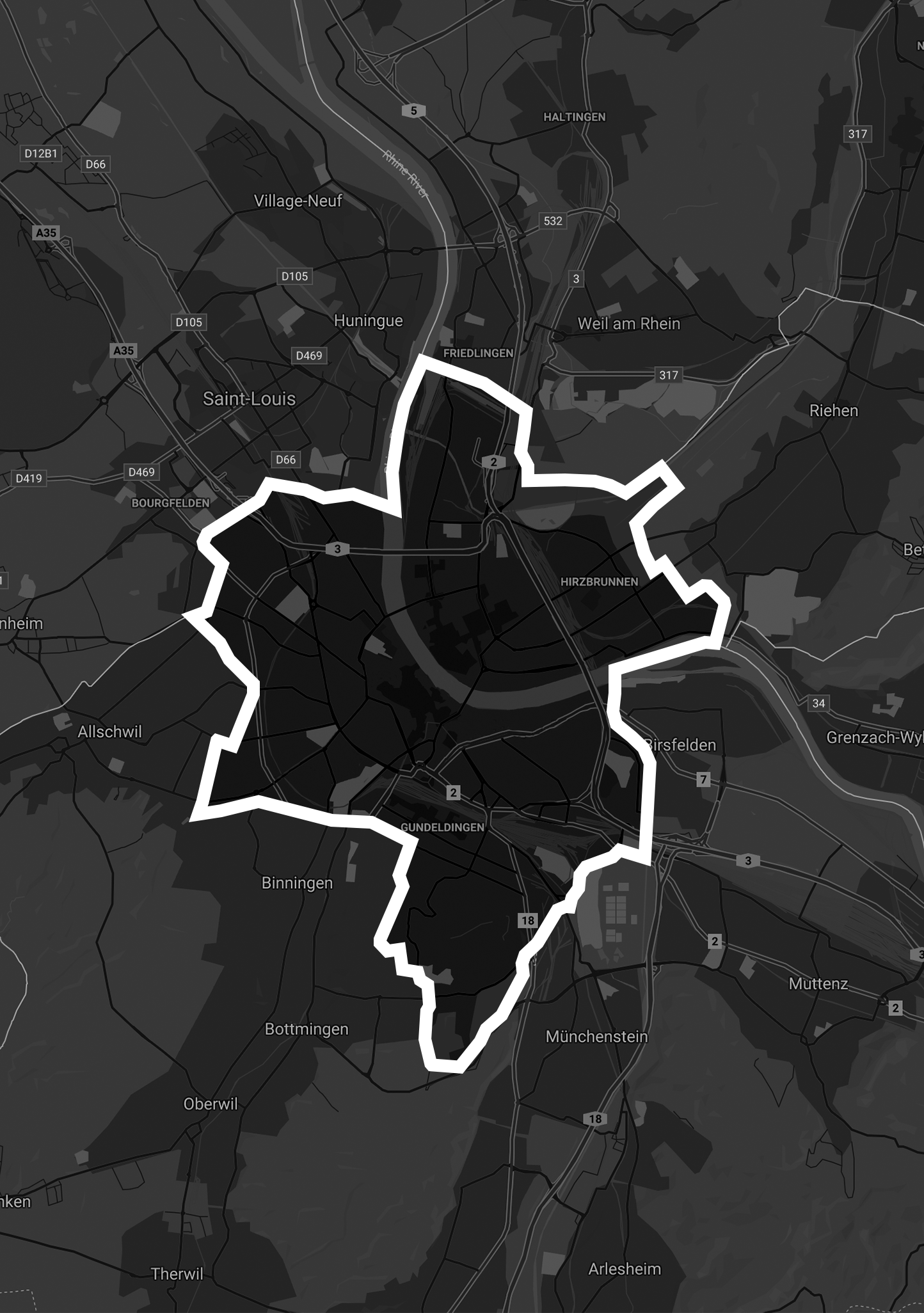

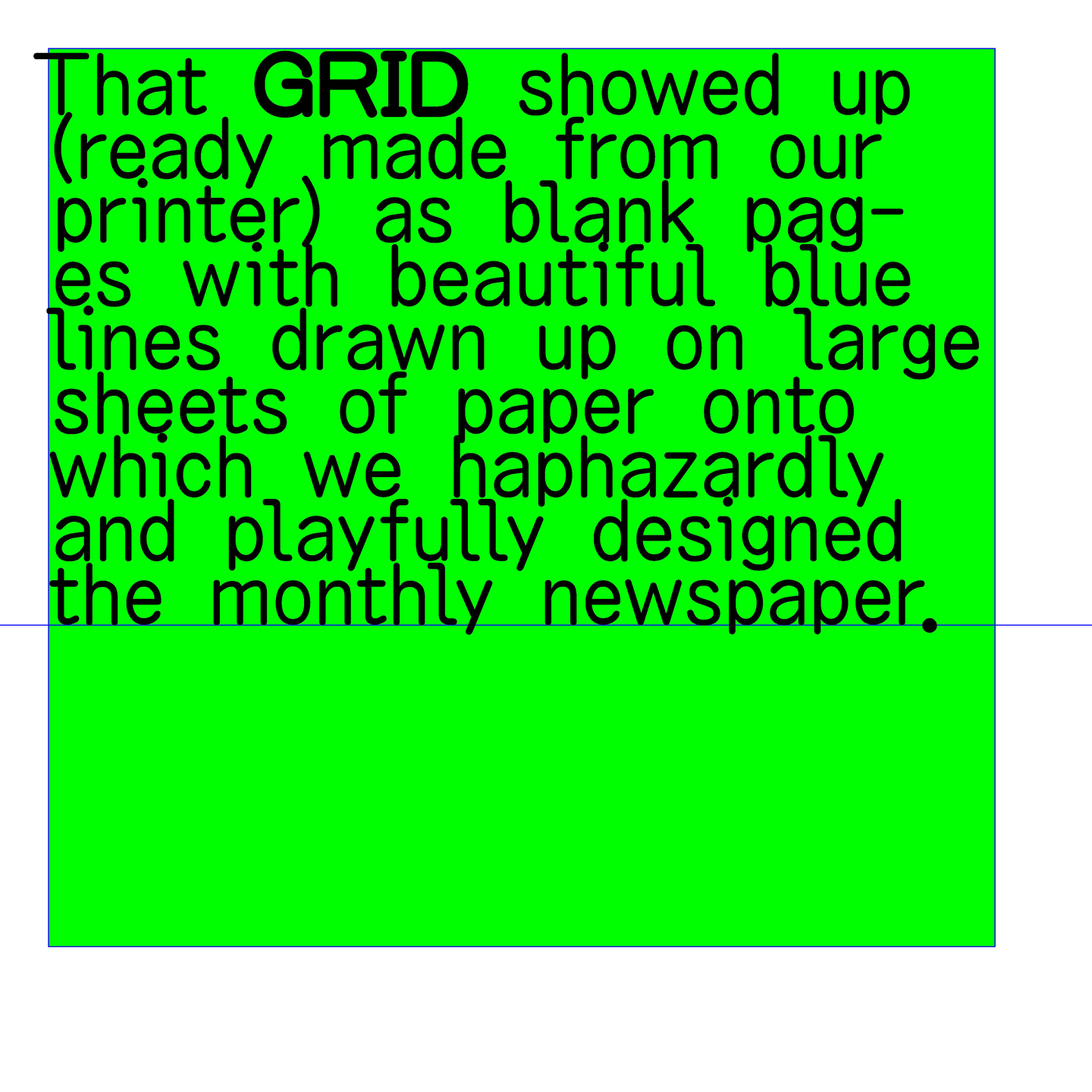

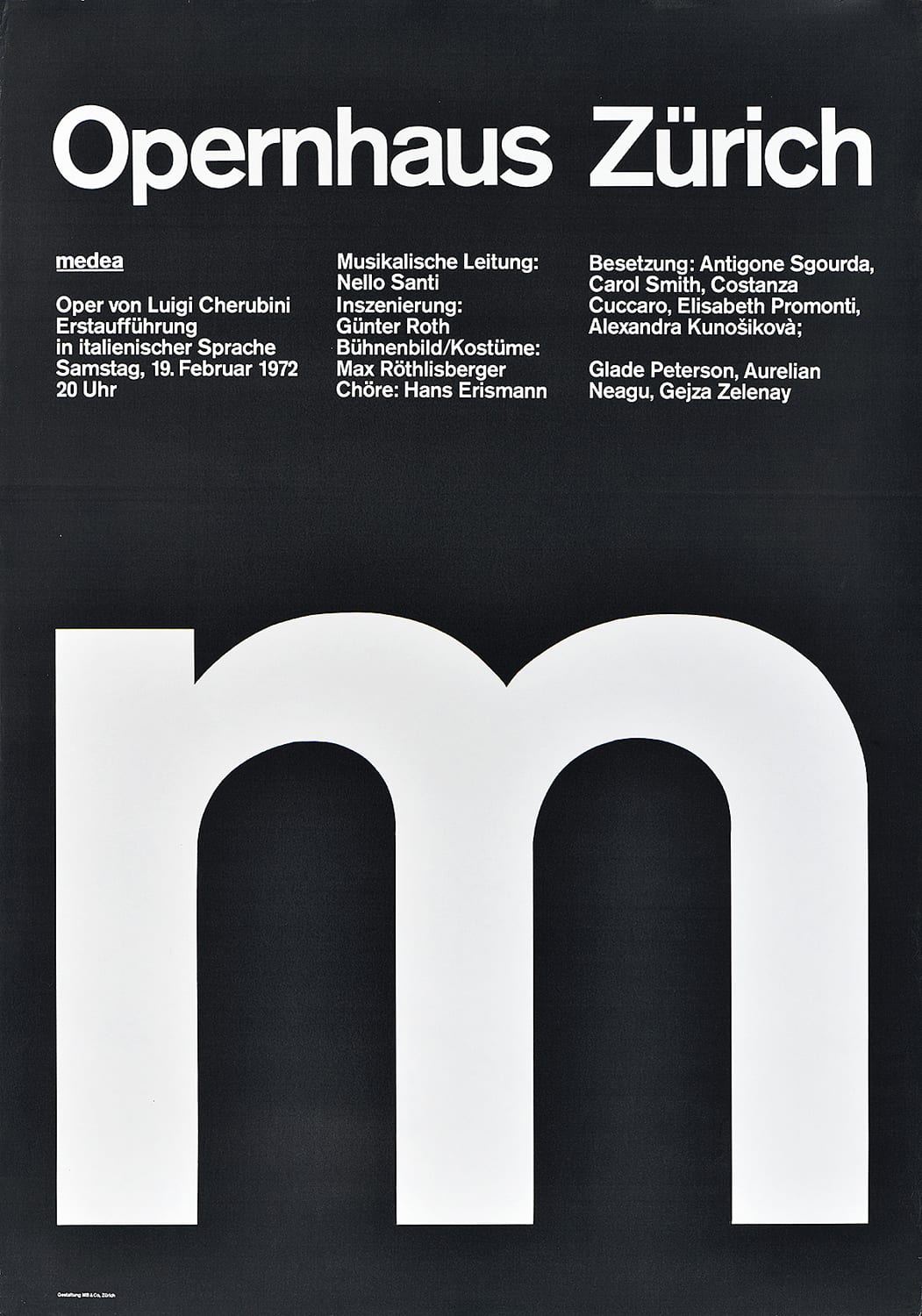

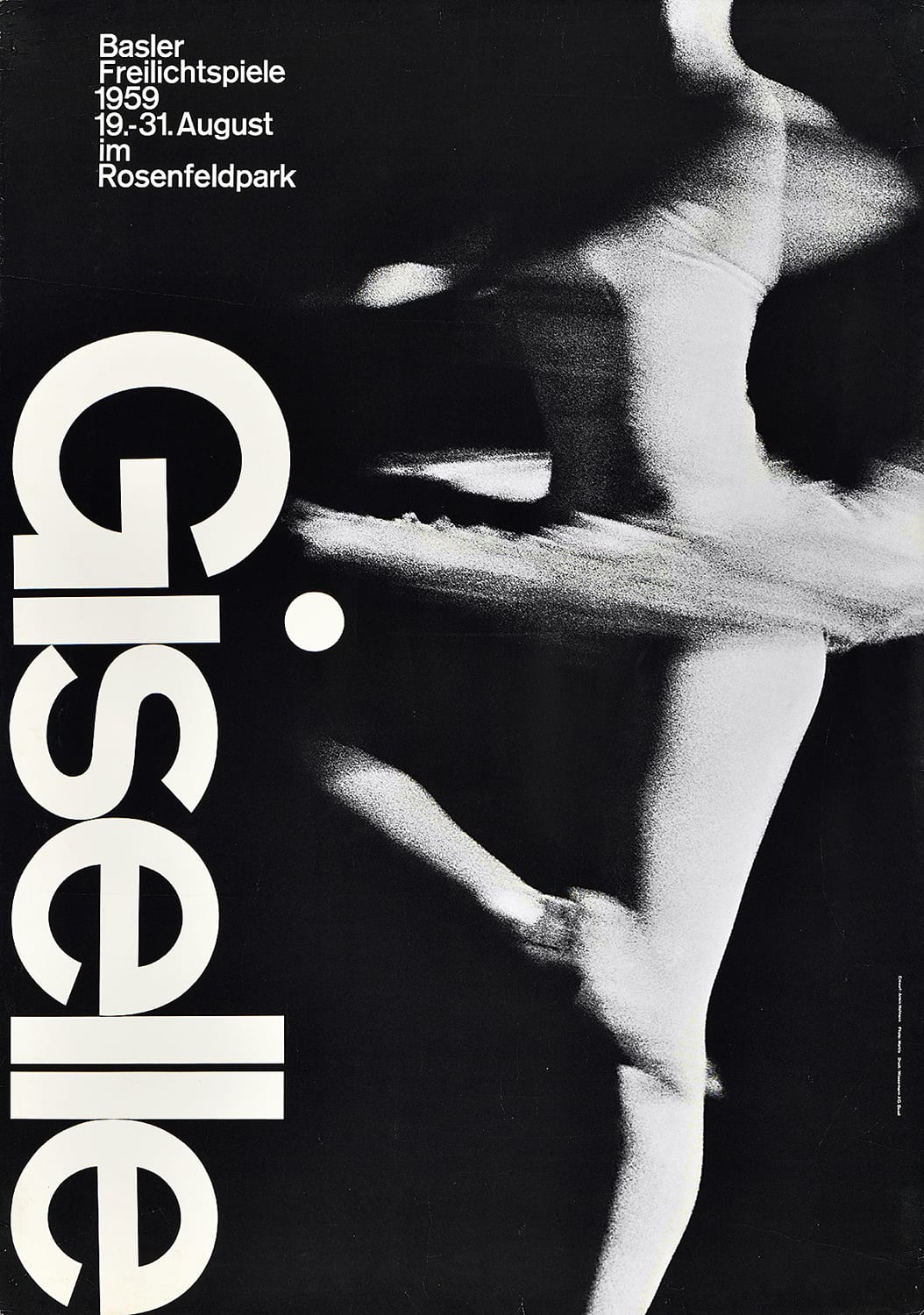

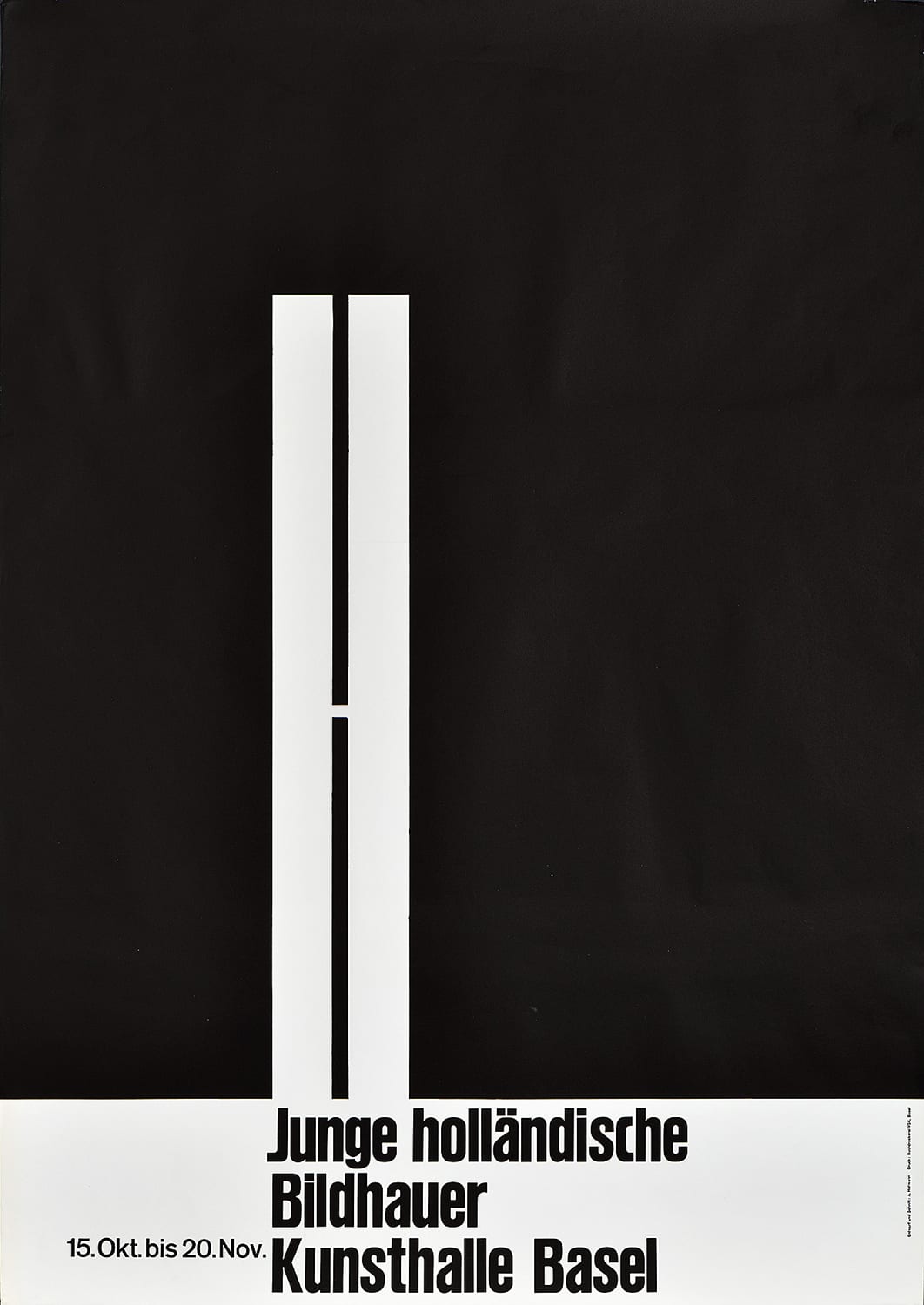

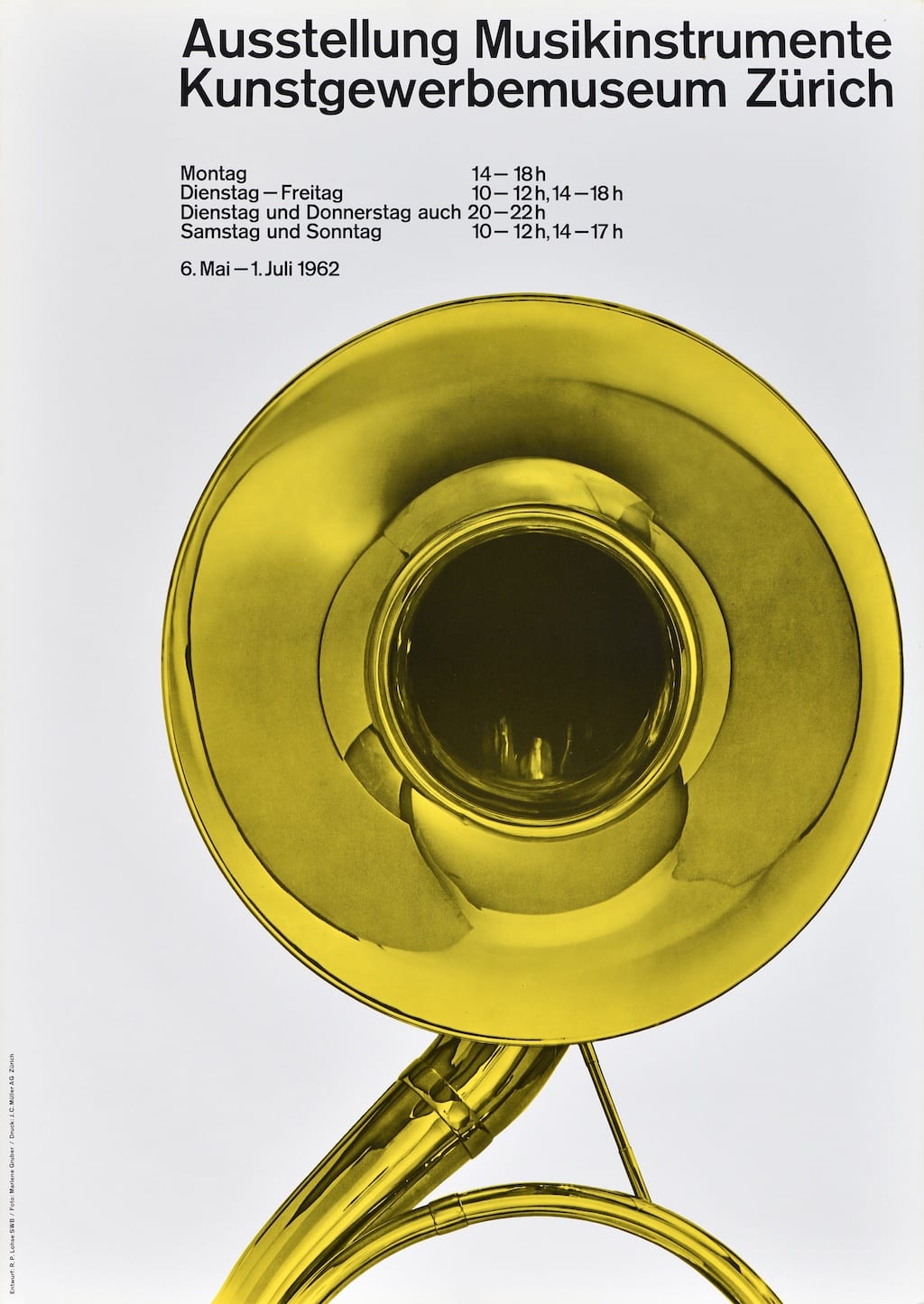

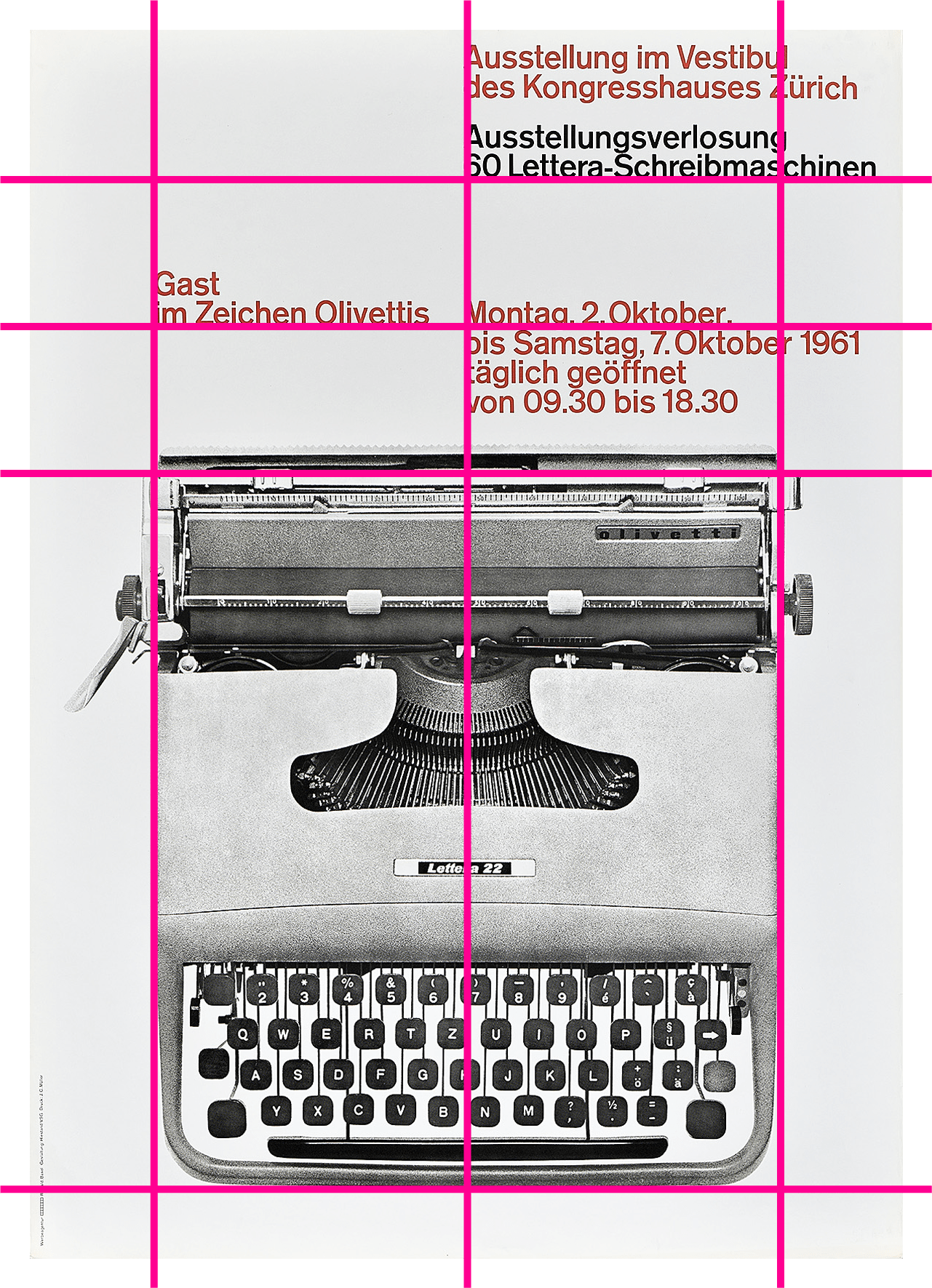

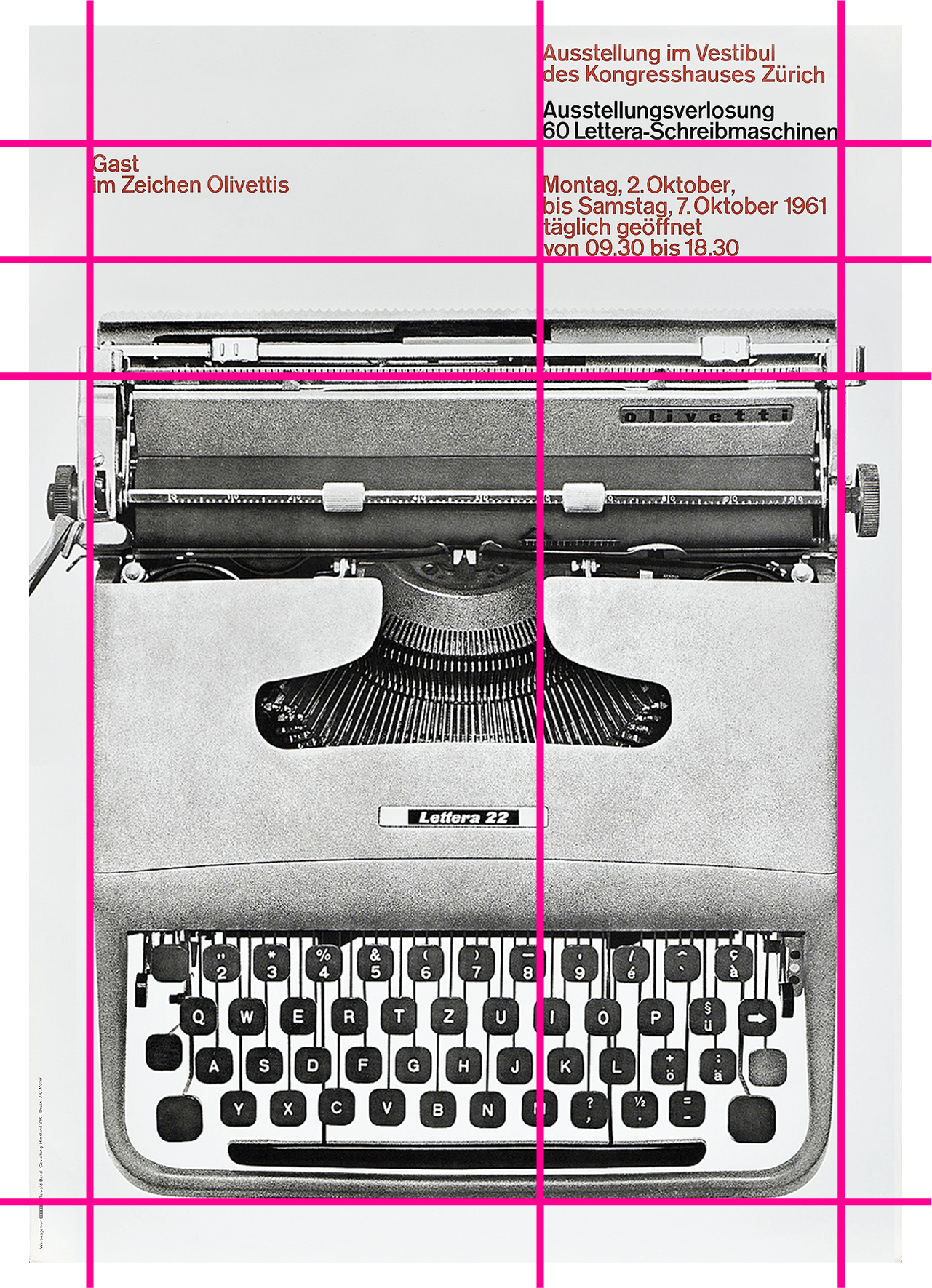

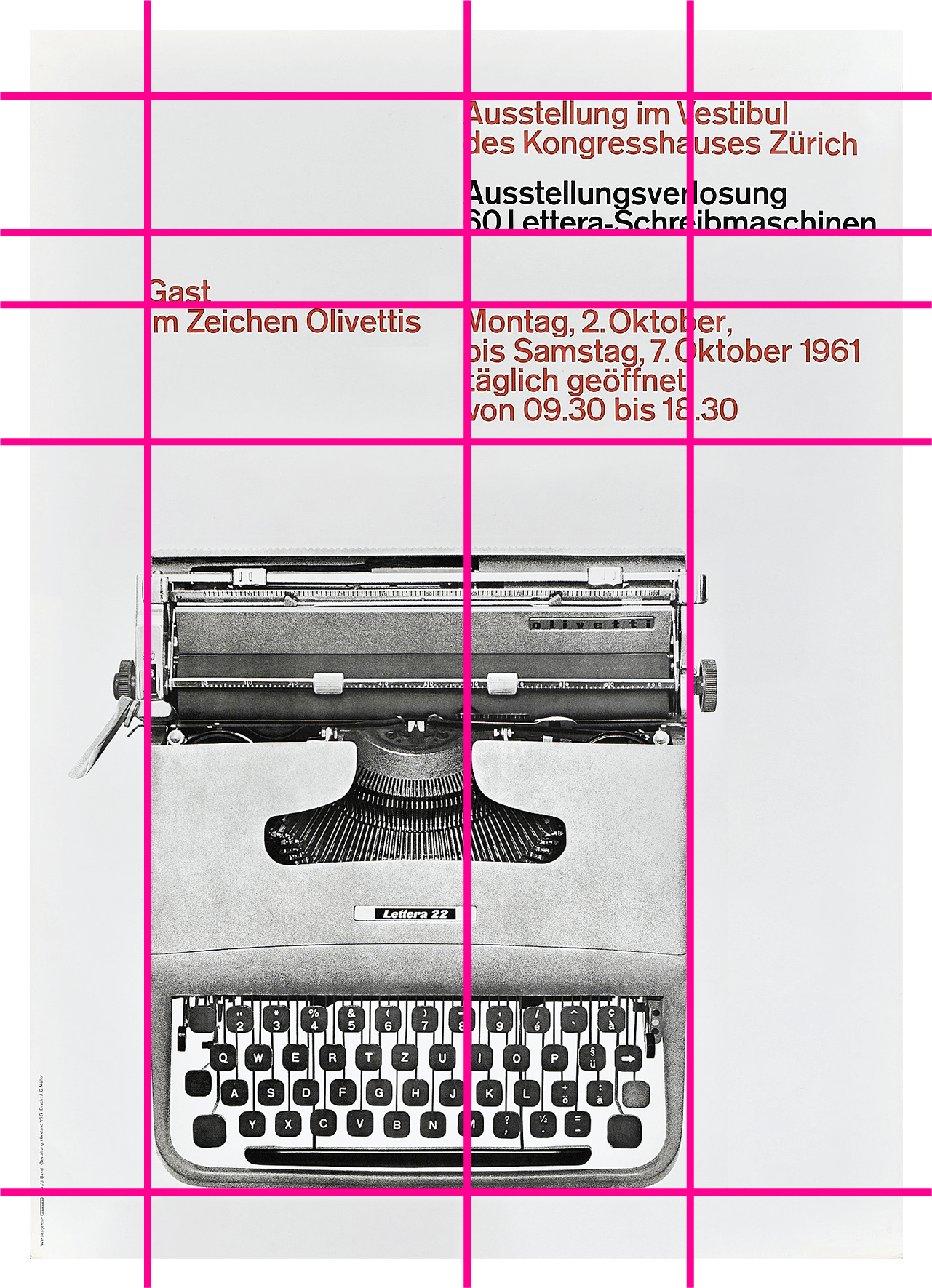

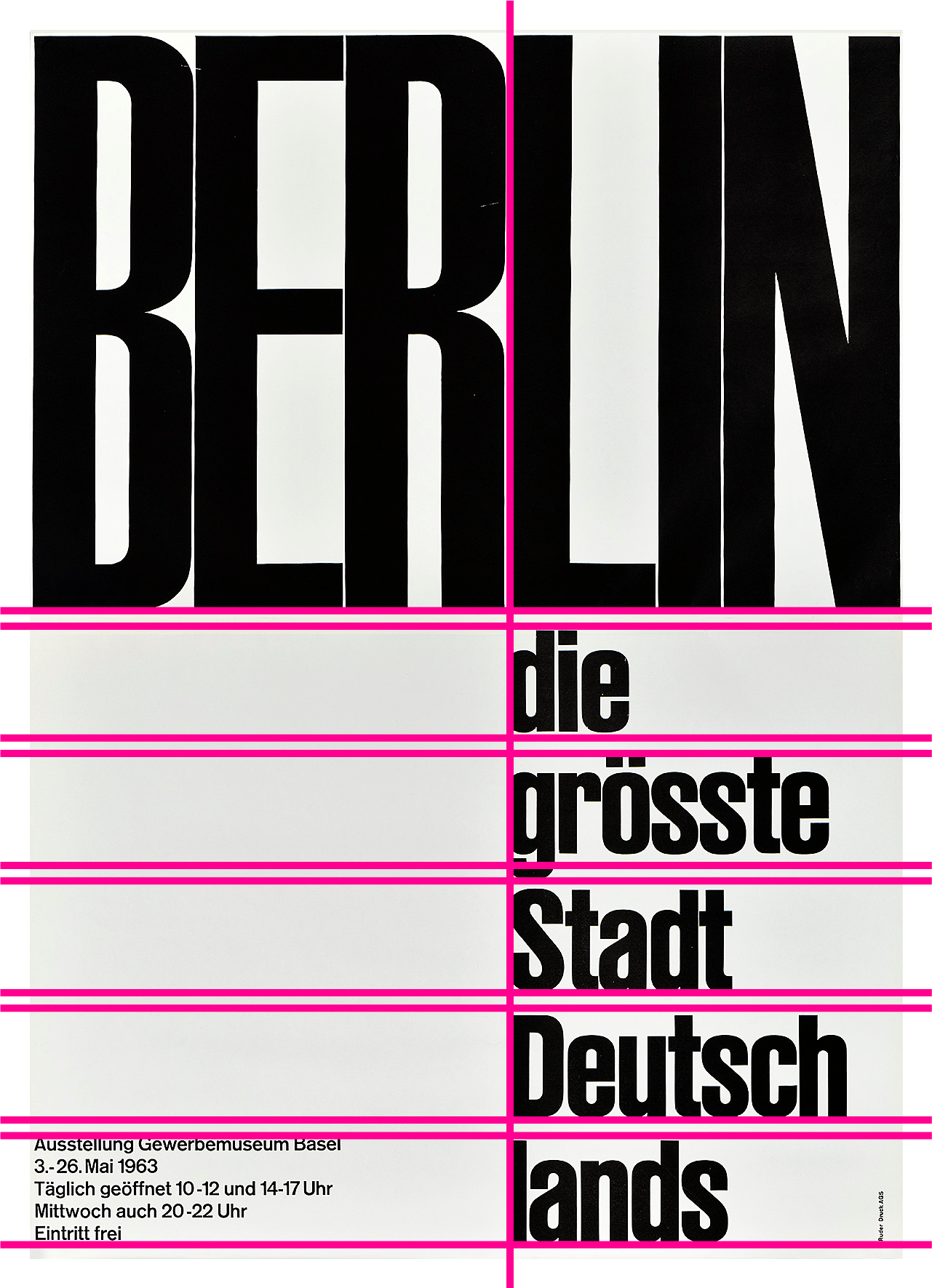

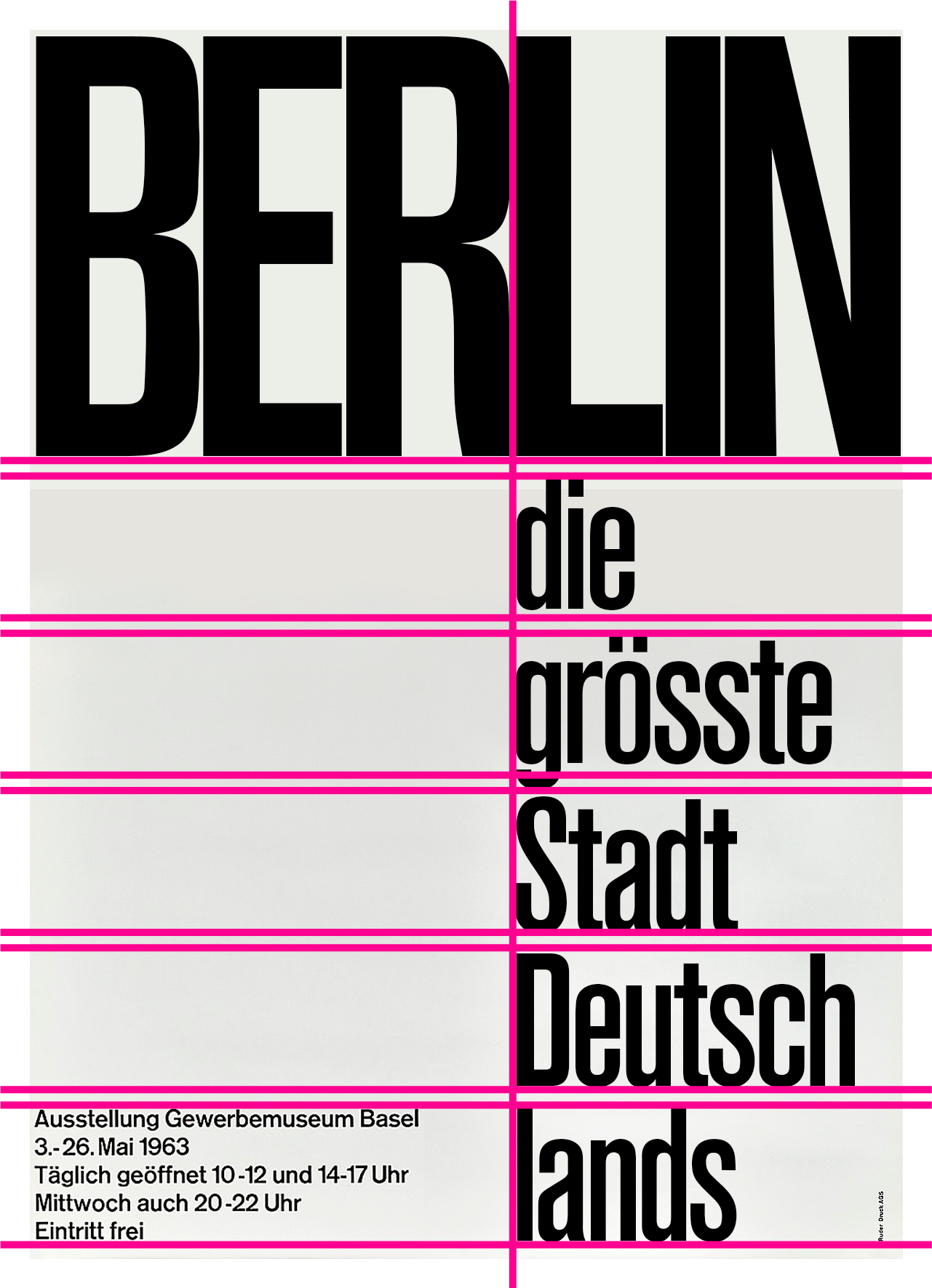

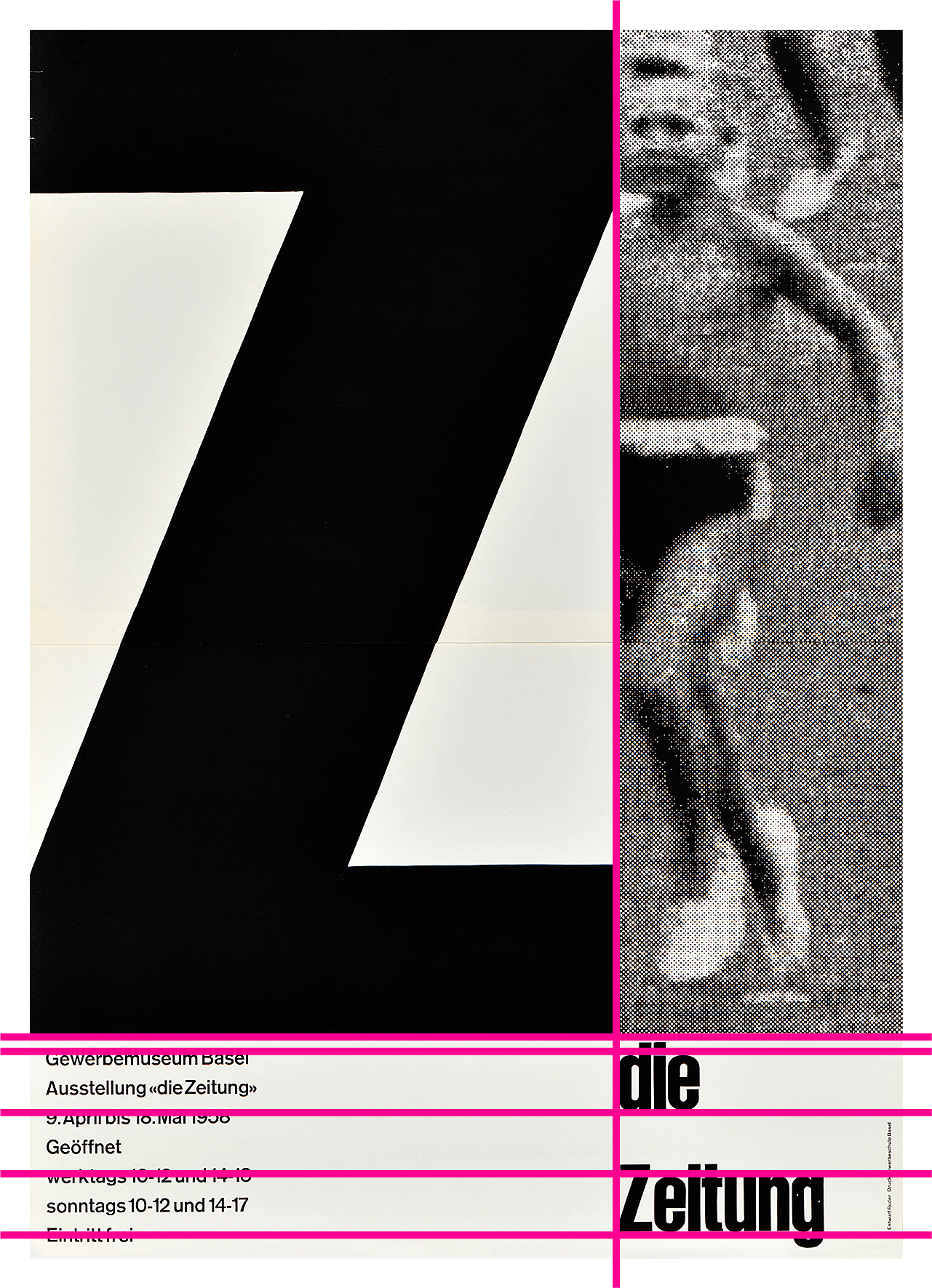

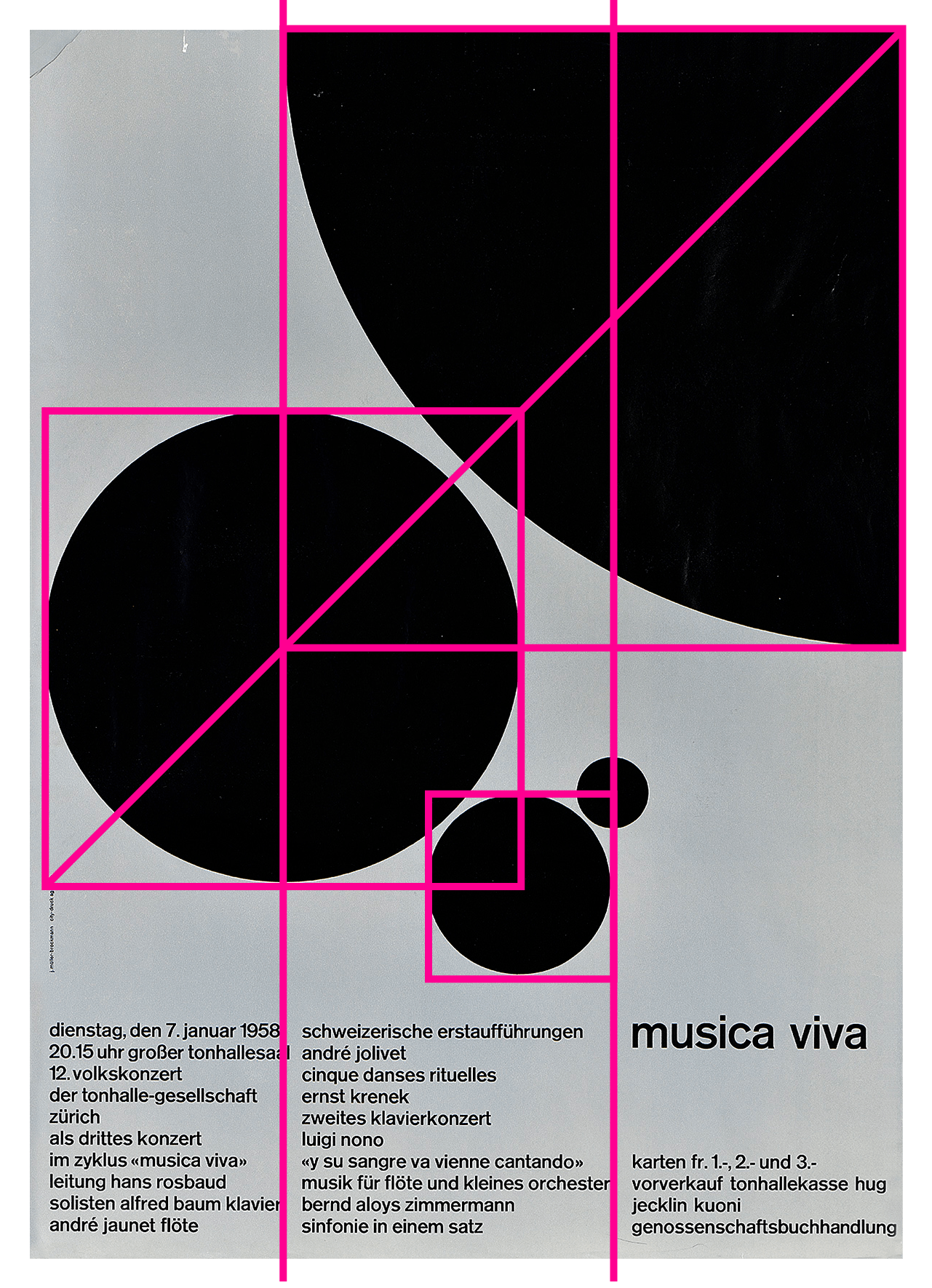

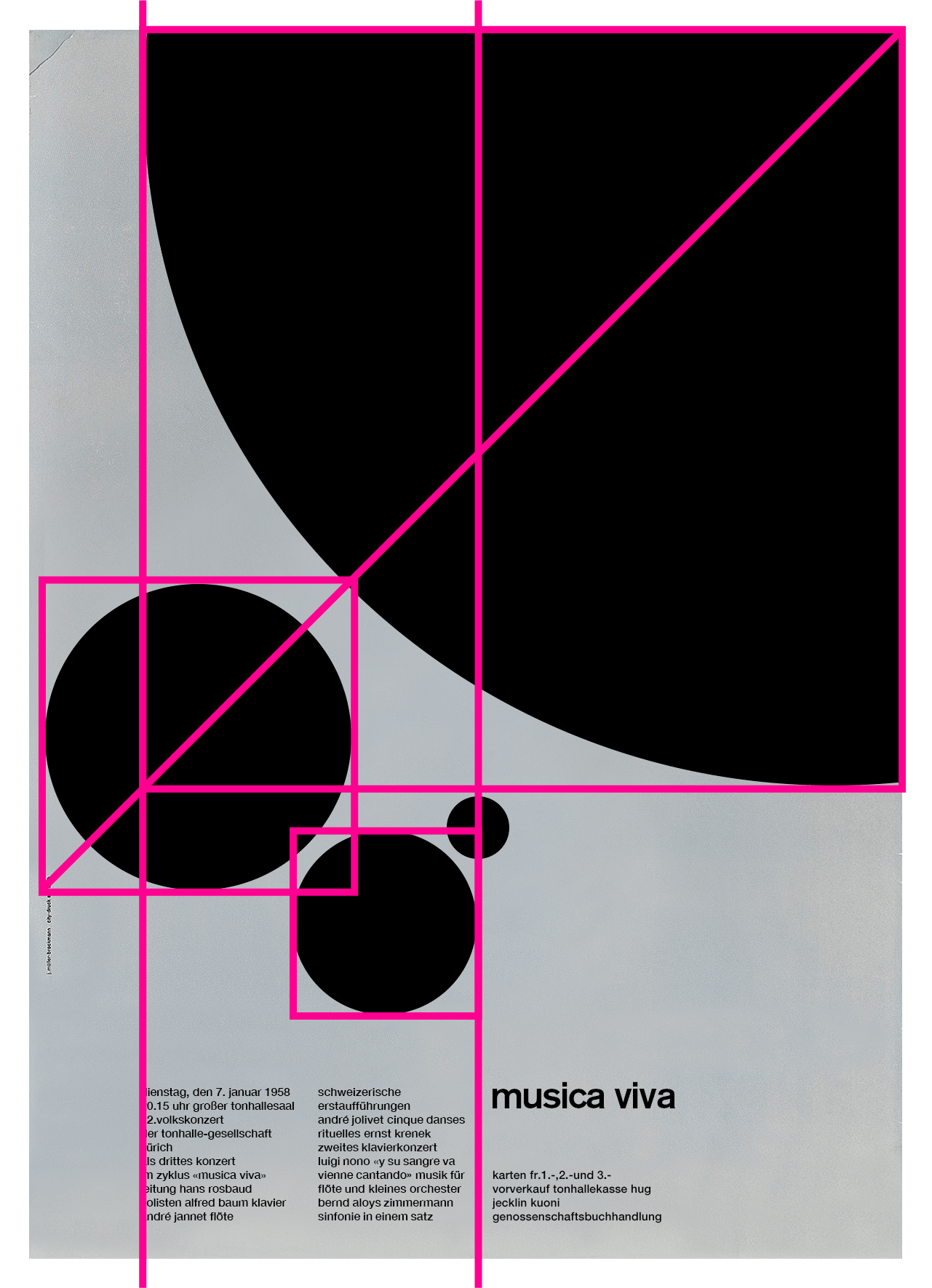

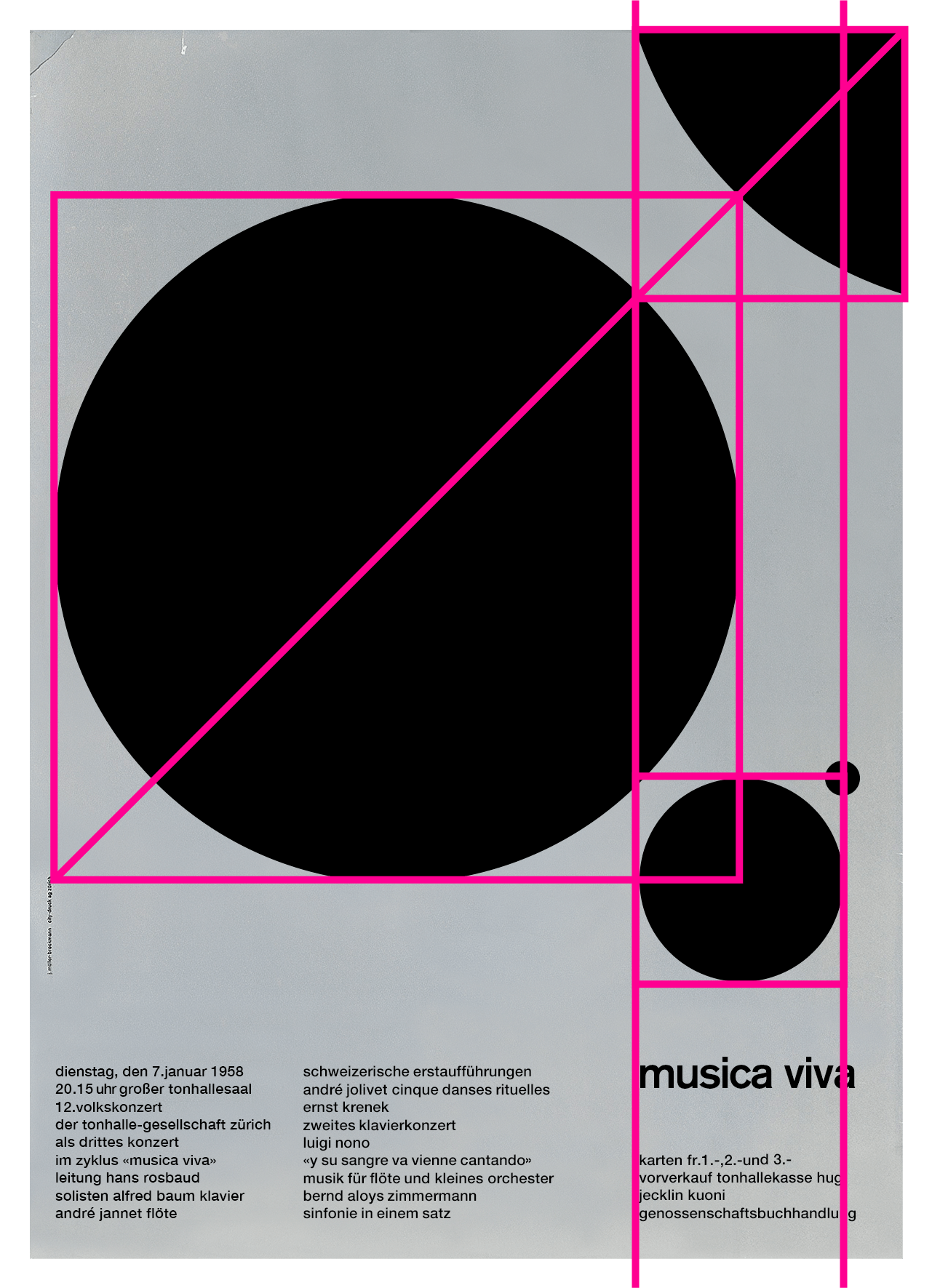

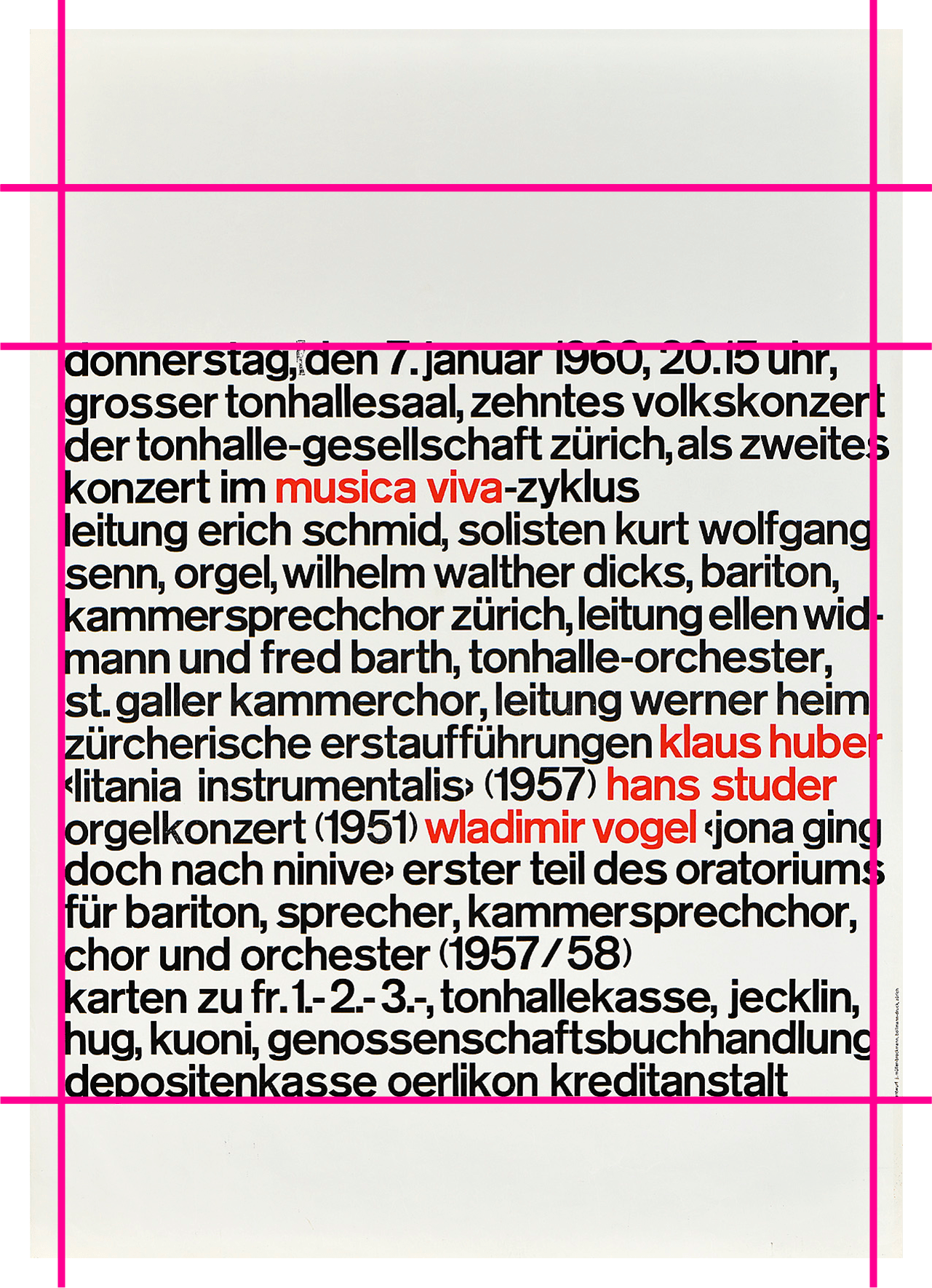

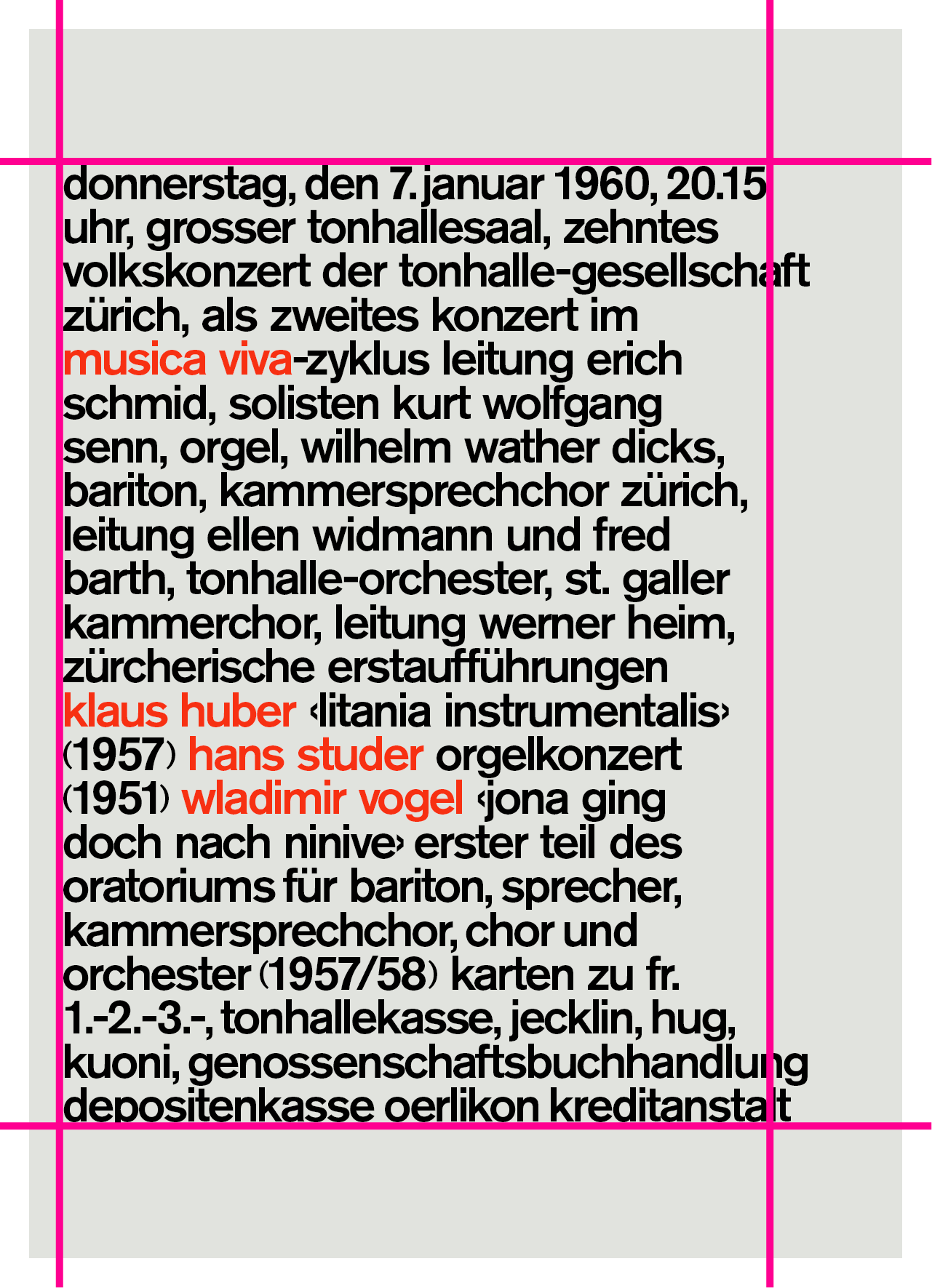

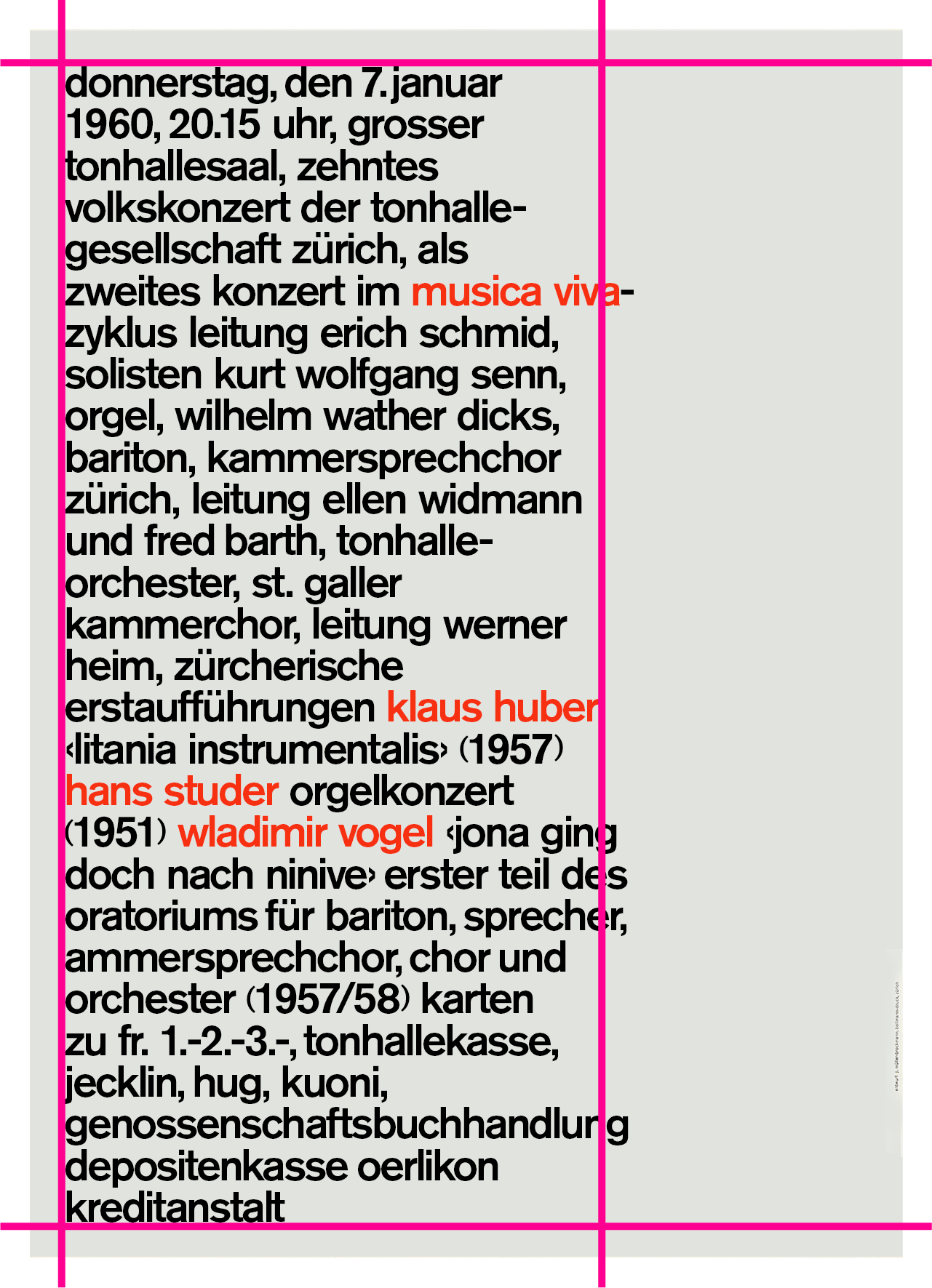

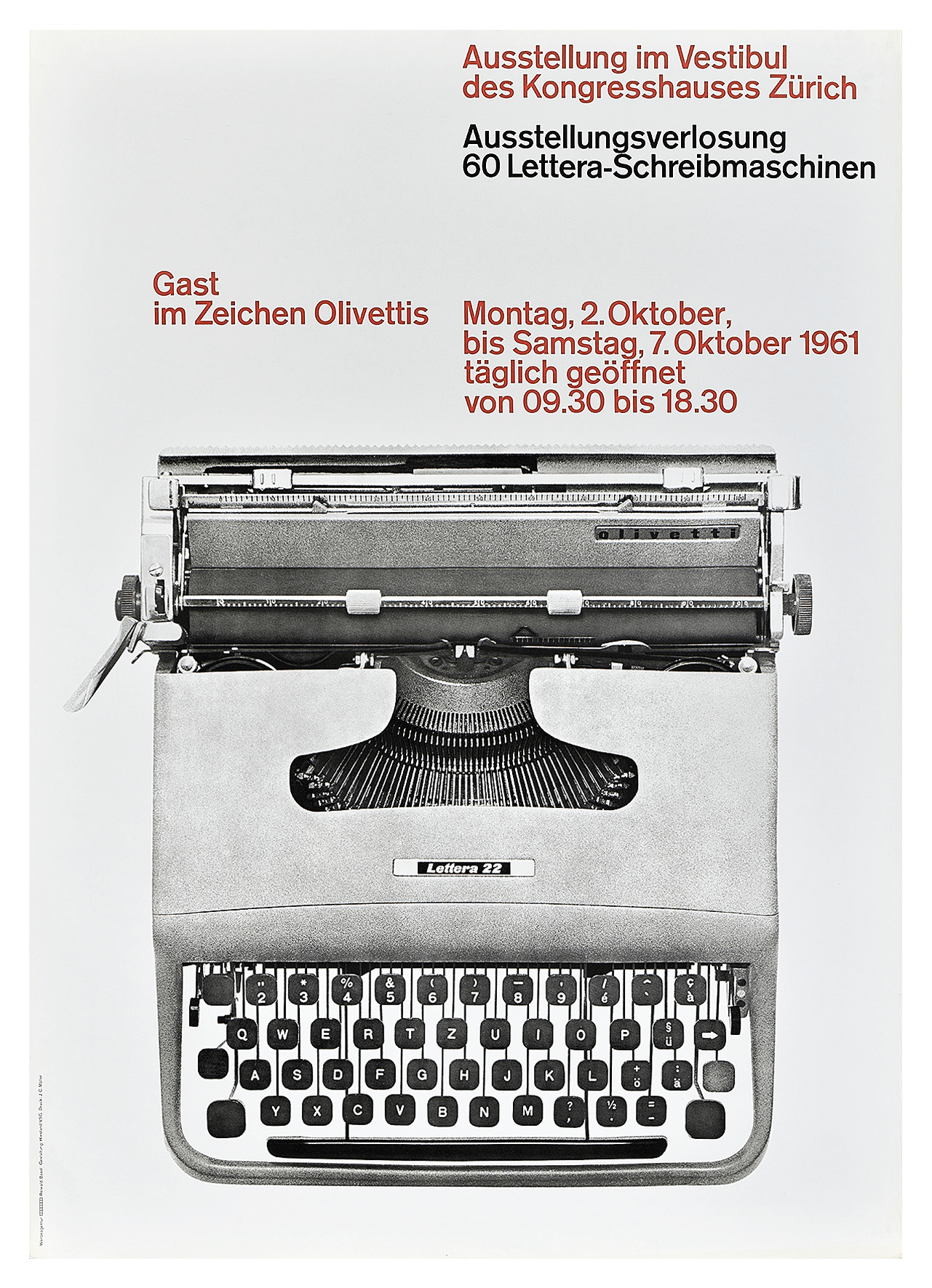

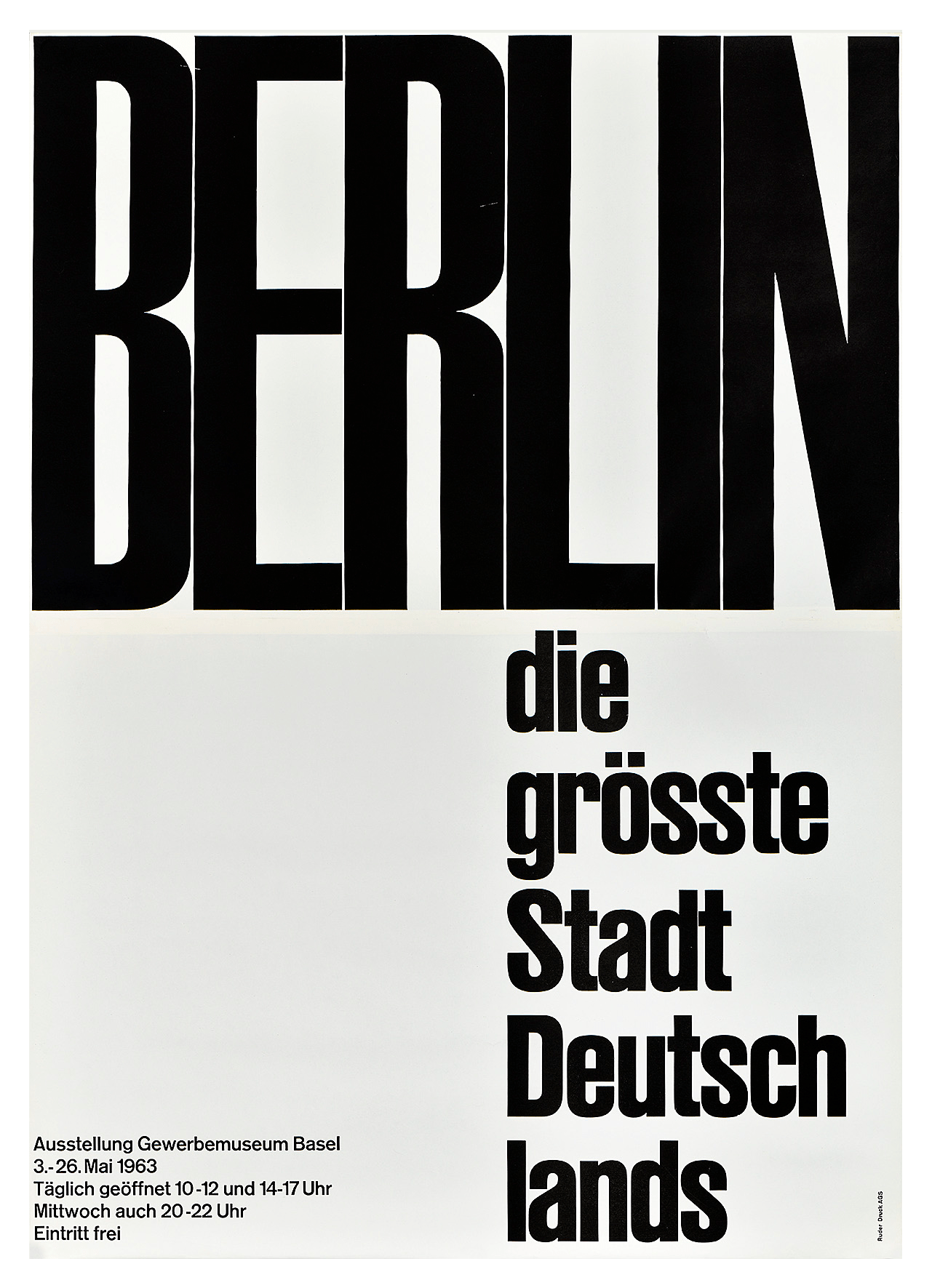

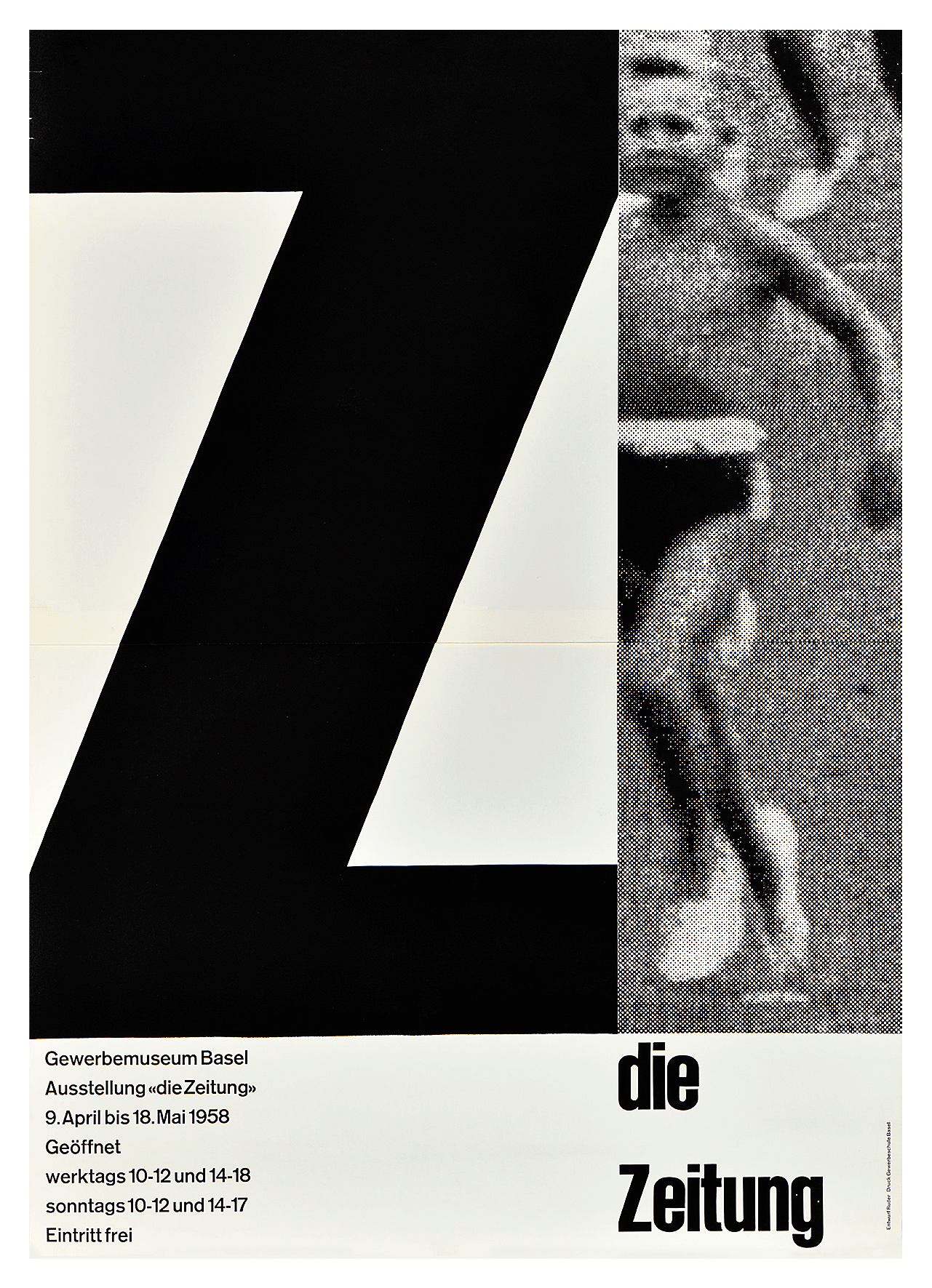

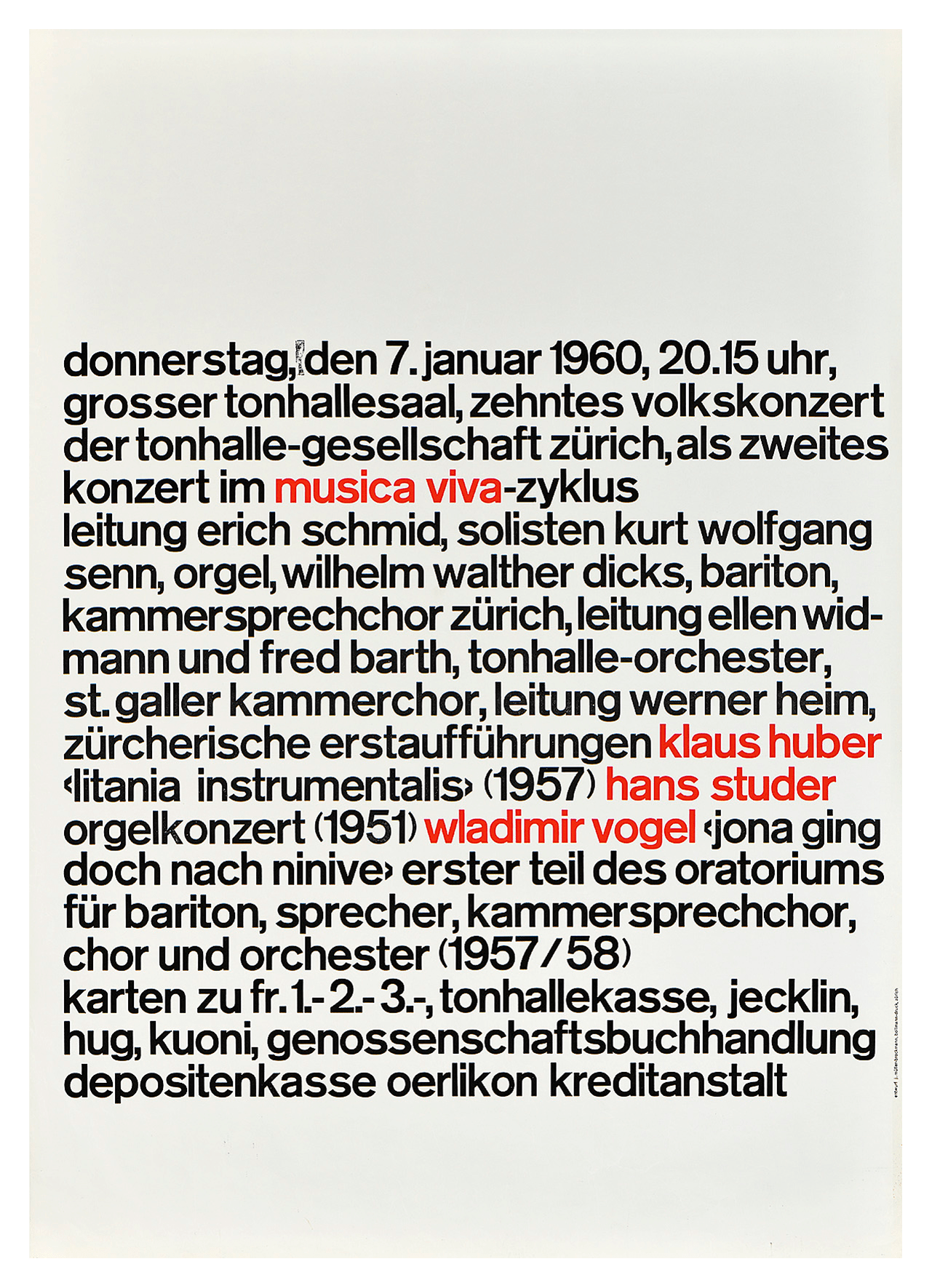

The Swiss Grid was an exhibition at Poster House in New York City that launched February 26, 2020. Ten days after opening, the museum shut down due to Covid-19. With input from designers and educators, Poster House transitioned the exhibition into a remote learning tool that provides historical and pedagogical context for some of the technical teachings of design.

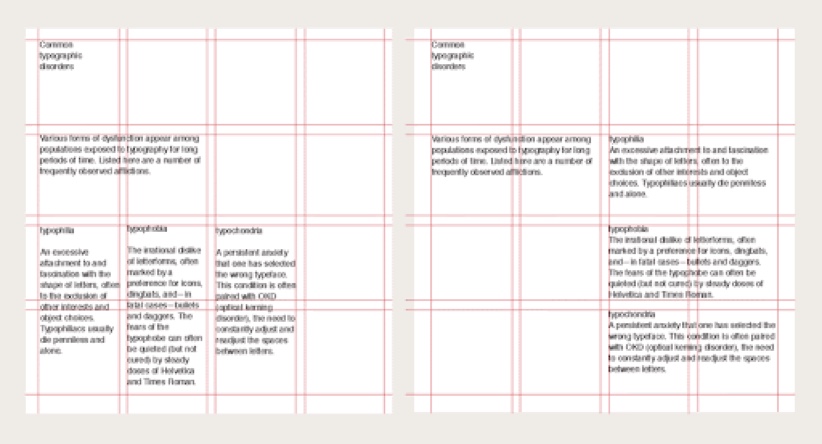

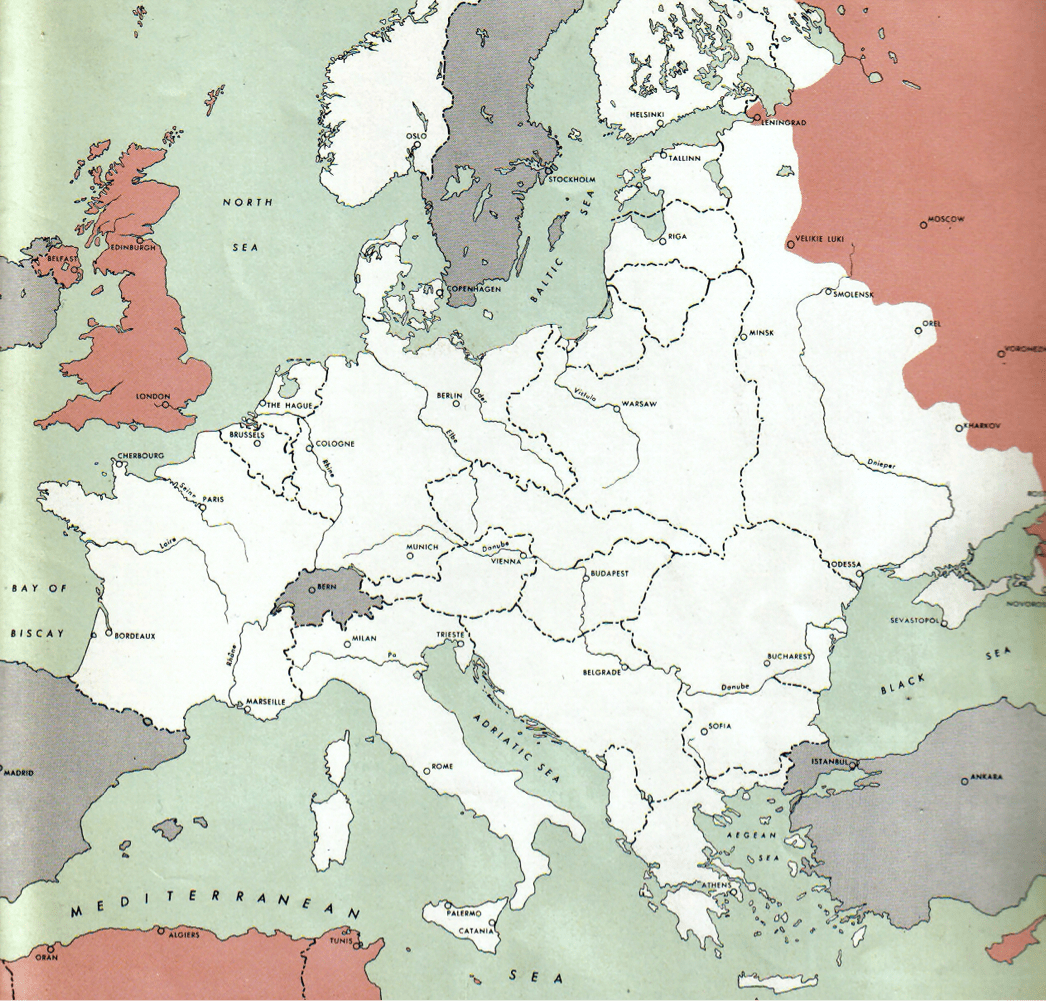

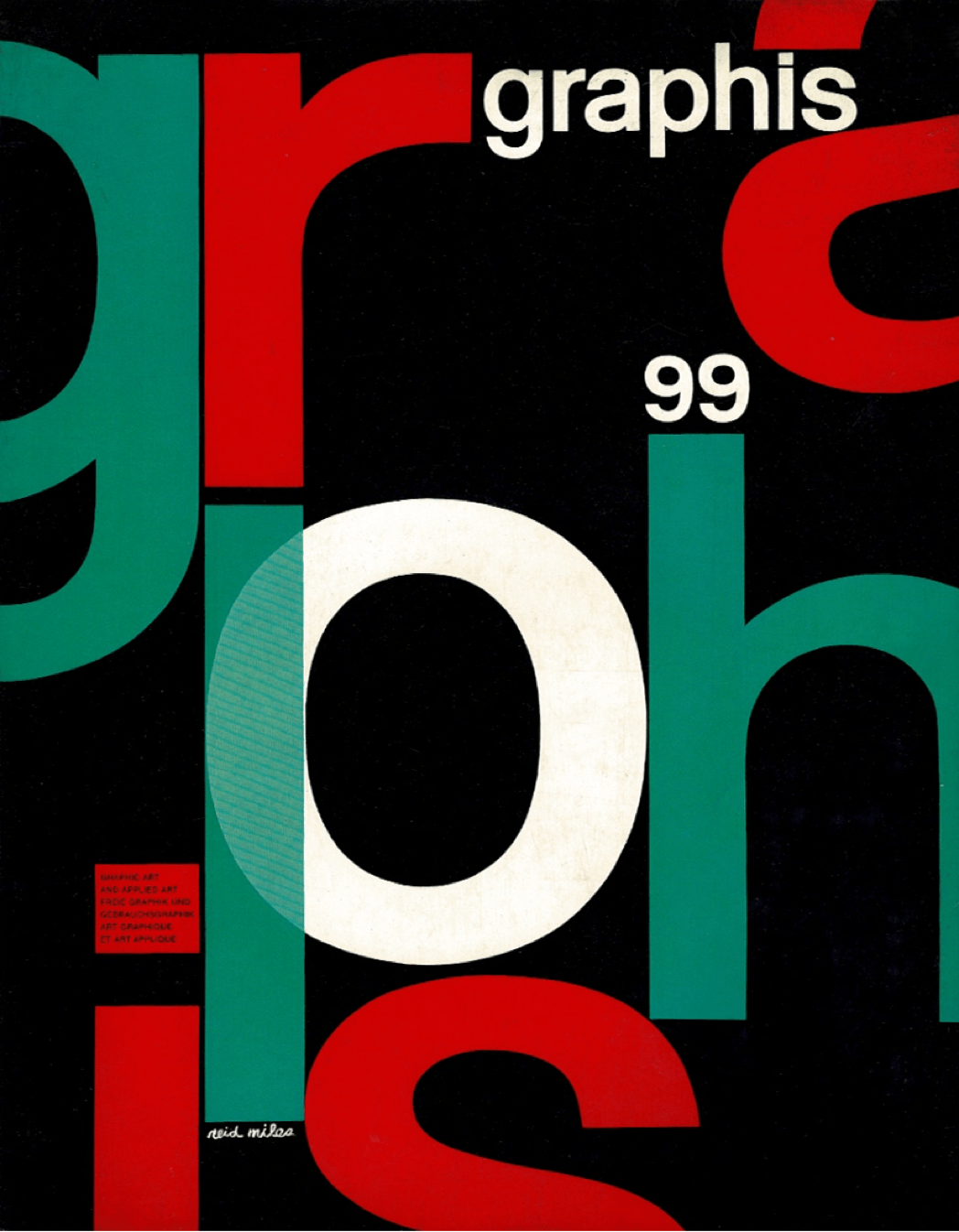

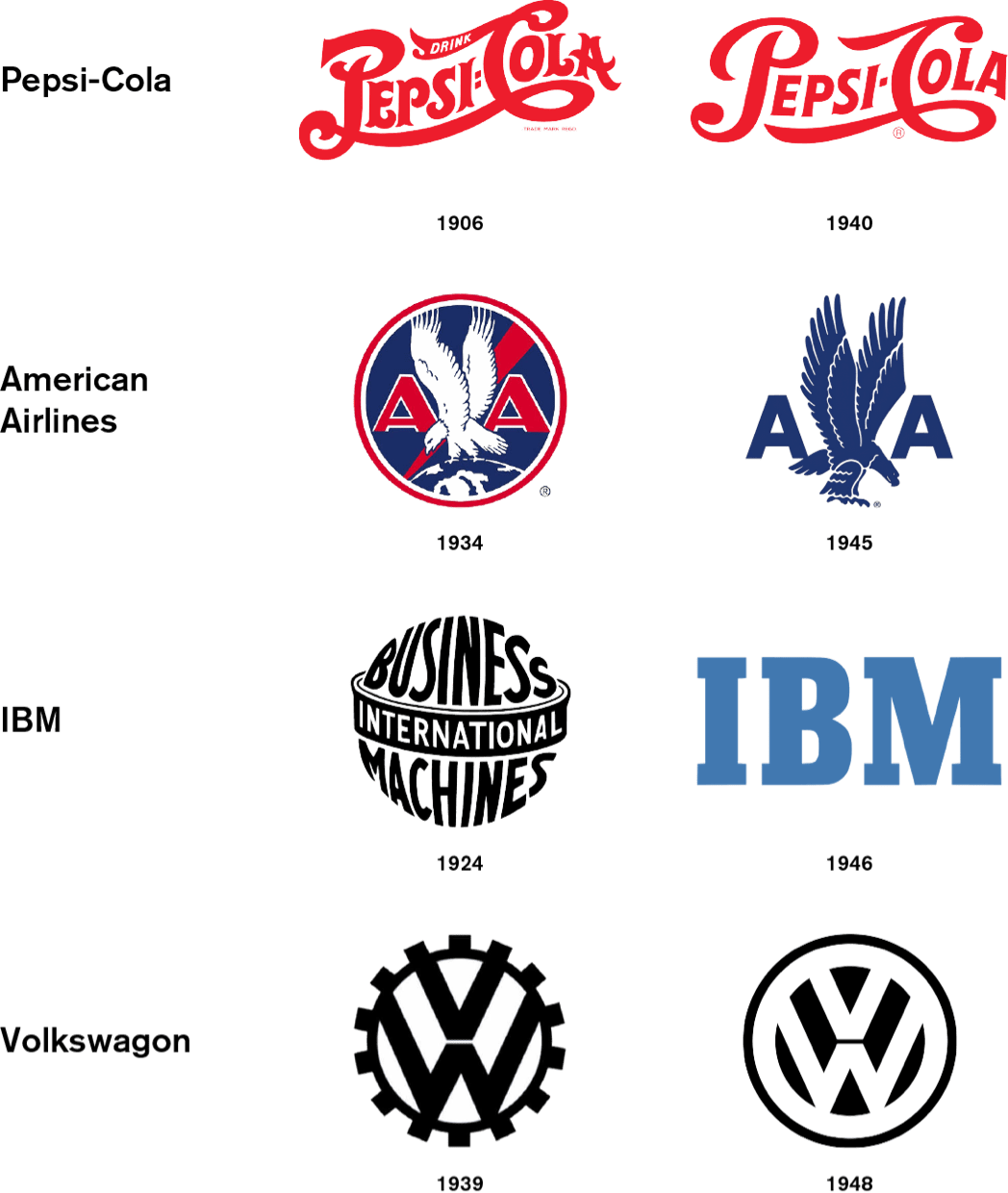

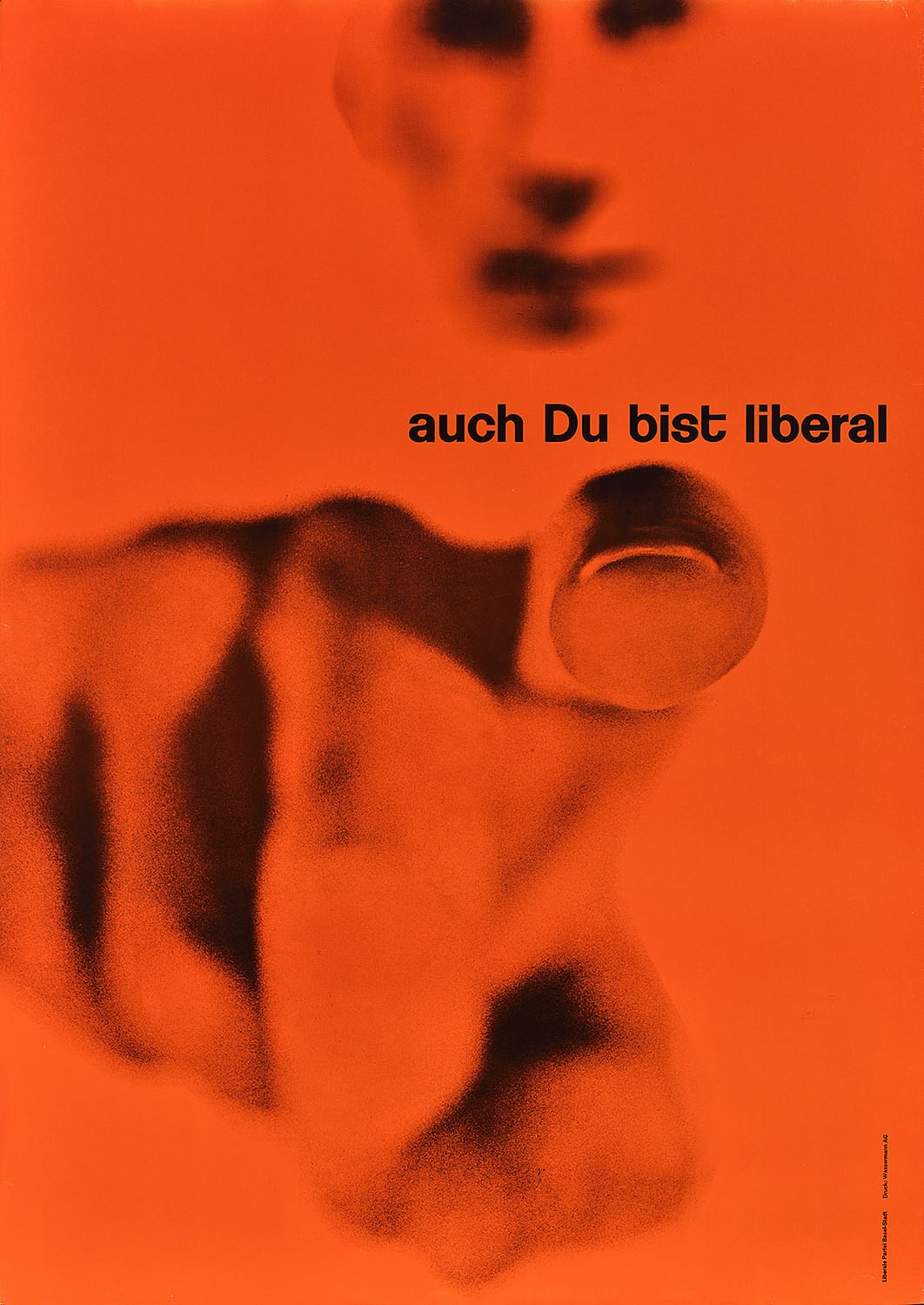

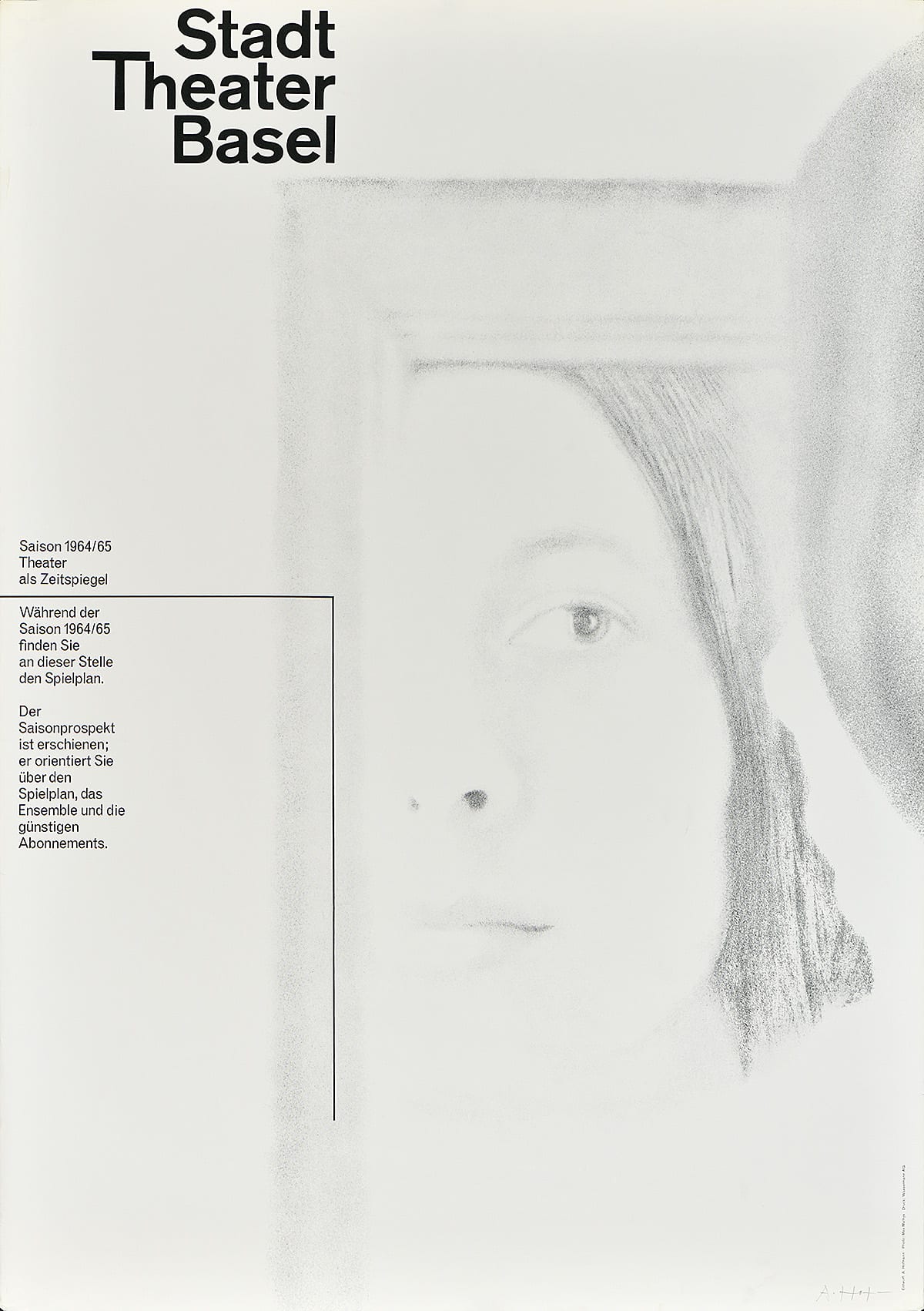

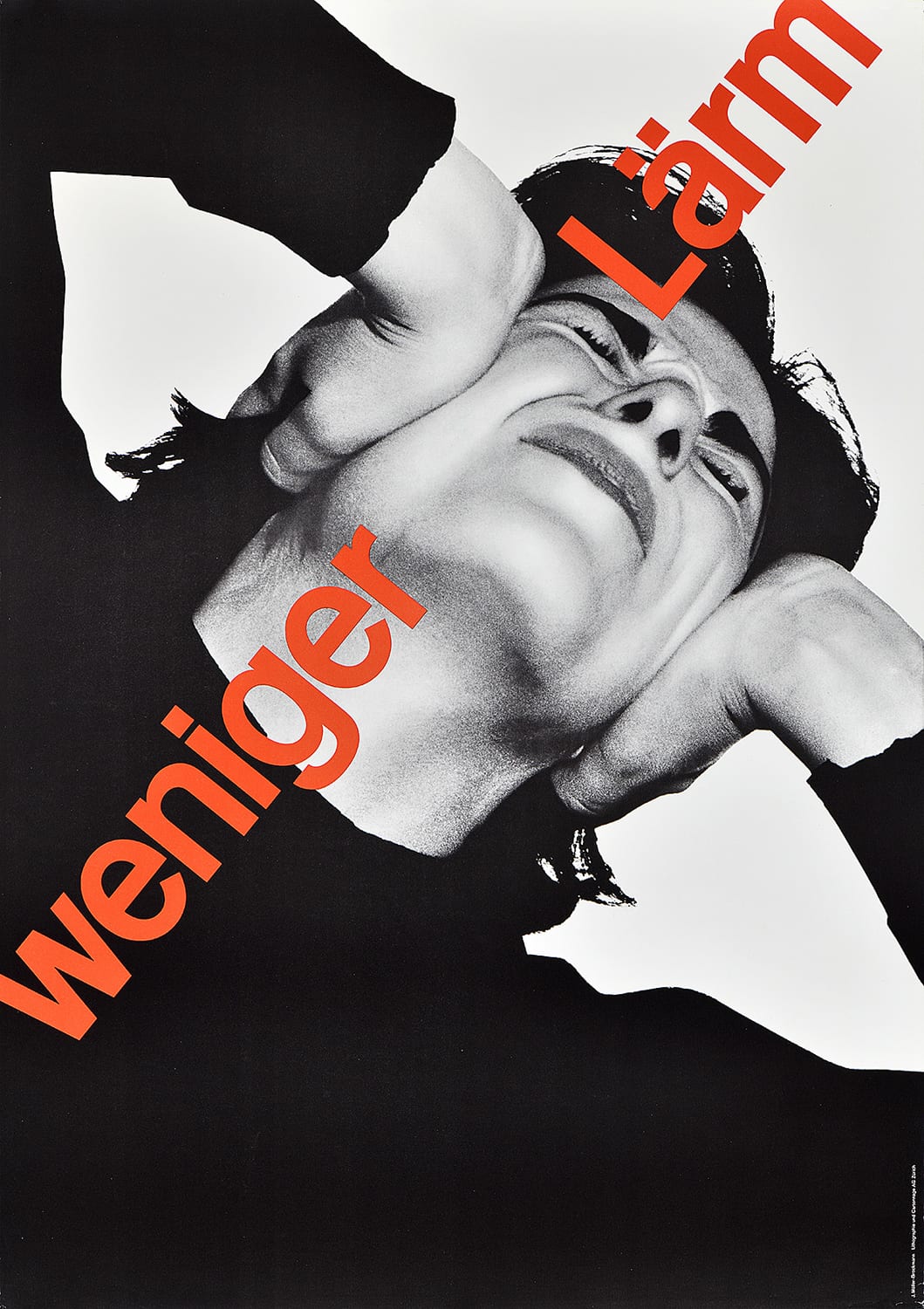

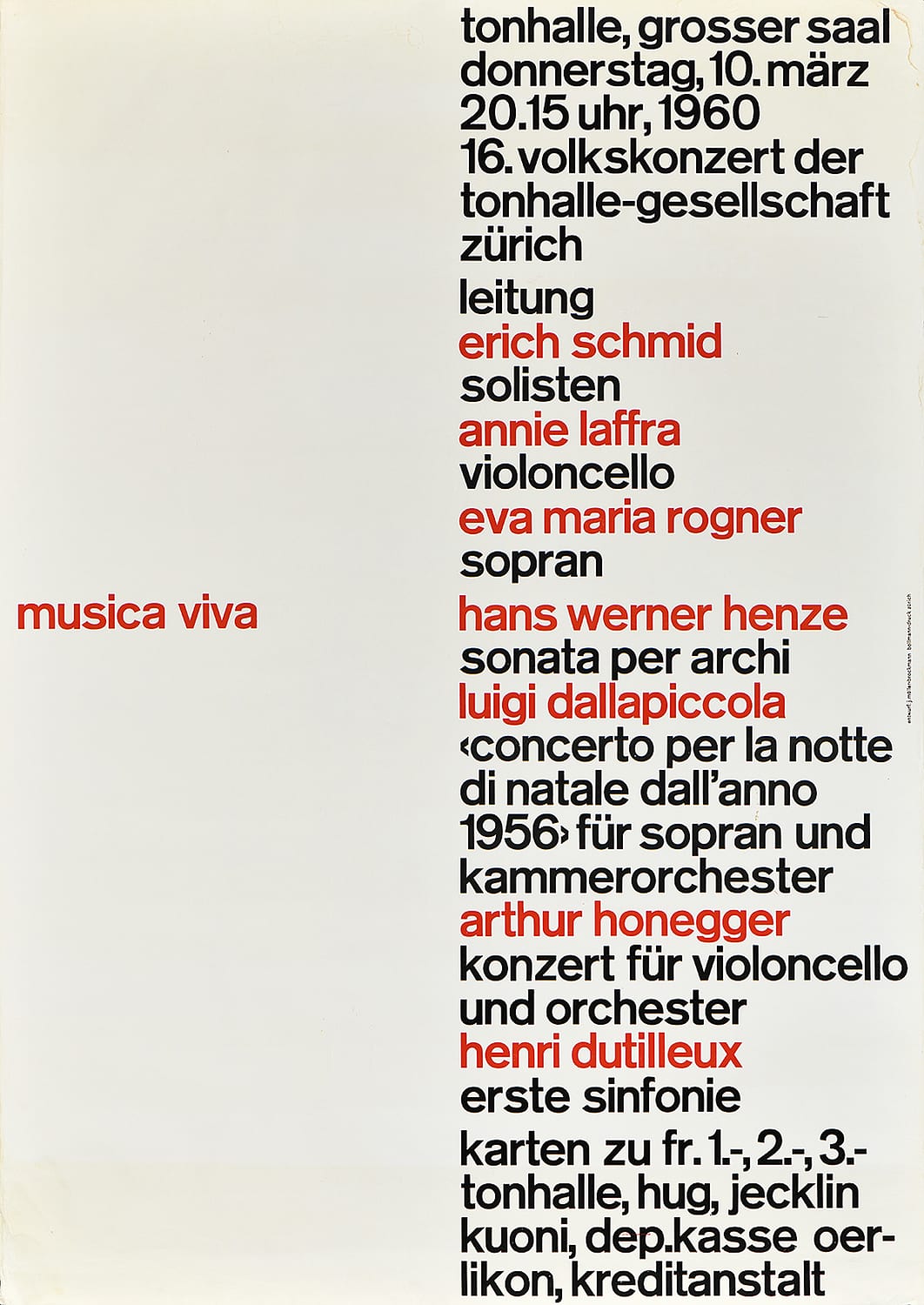

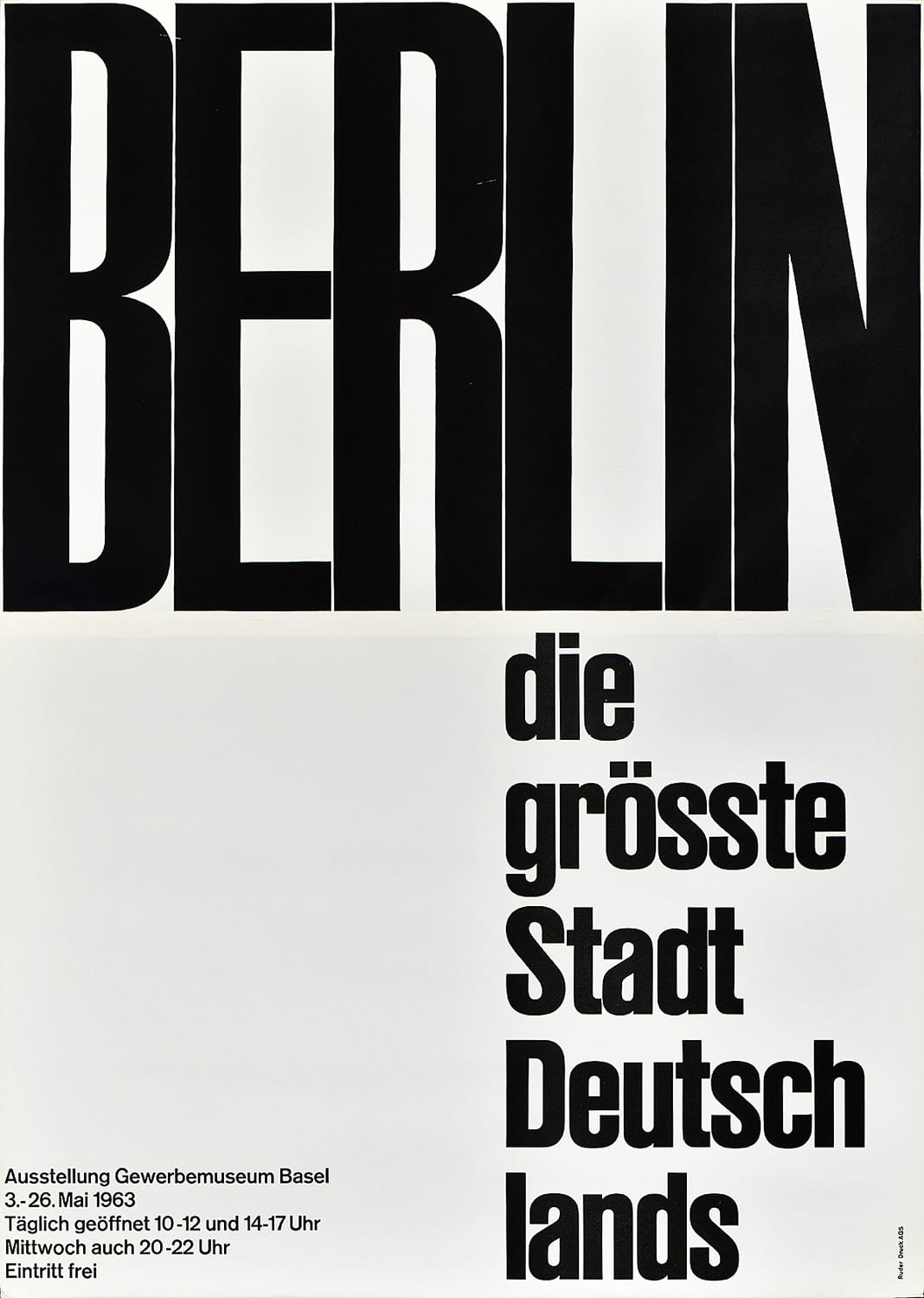

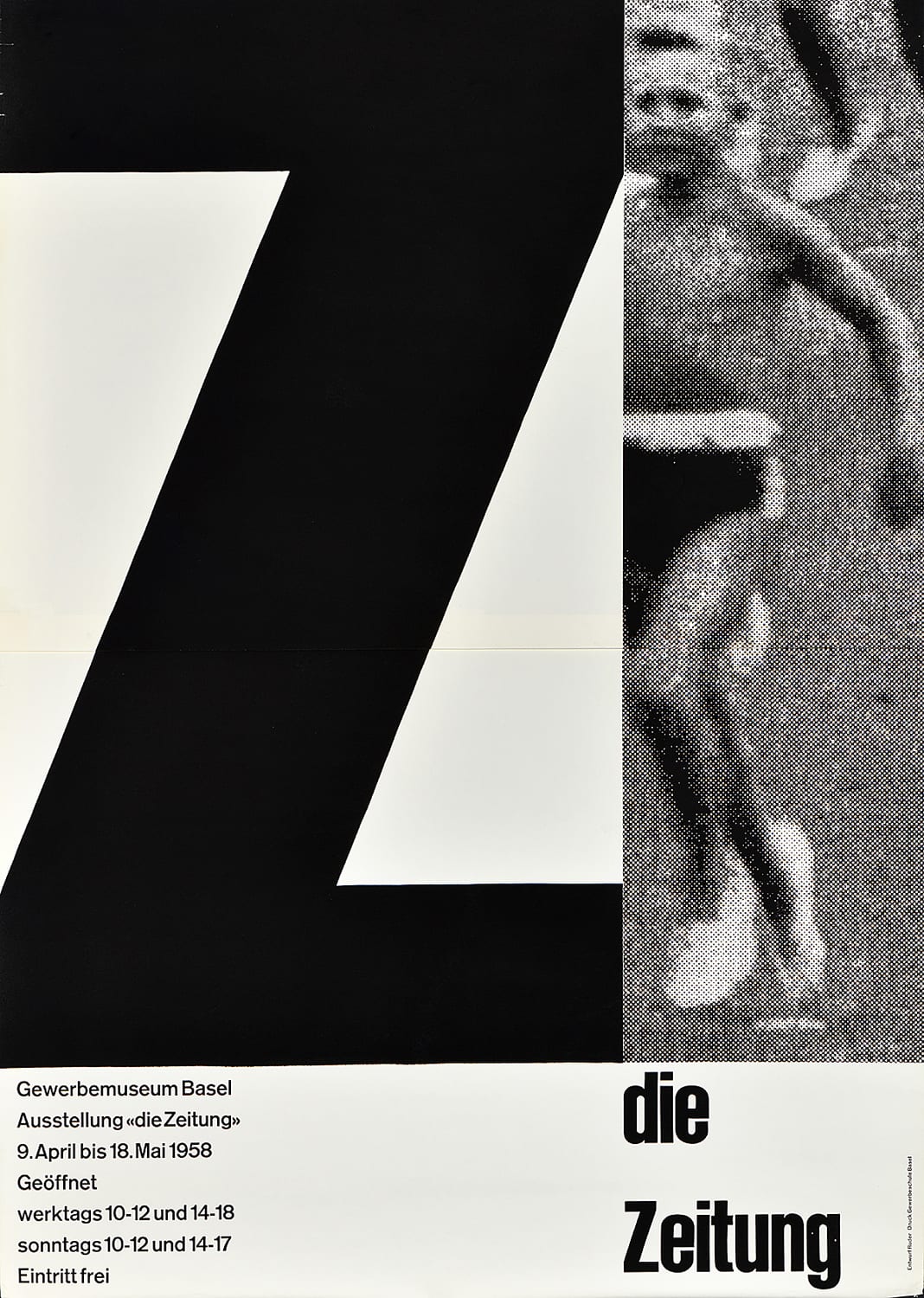

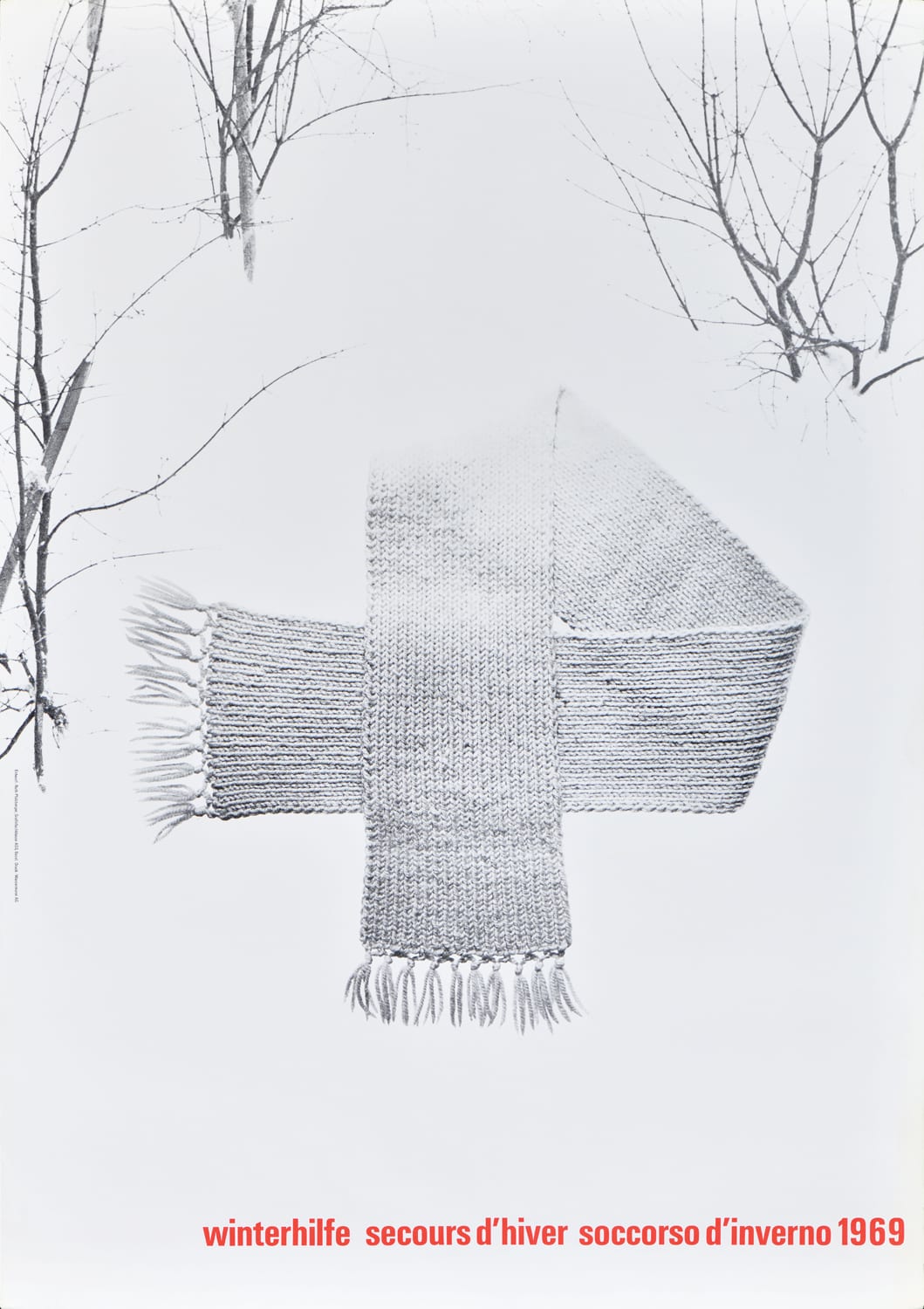

Using the core material from the original exhibition, this site considers how a particular aesthetic—referred to throughout as “The Swiss Grid”—developed out of post-WWII Switzerland and spread around the world through generations of practitioners, and how the grid was used to create incredible posters for the cultural sector. This microsite interweaves contemporary attitudes towards teaching mid-century Modernism and the desire to both break free of and find new use for grid systems in contemporary design.

Audrey Bennett

MDes Program Director and Professor, Stamps School of Art & Design

Commentary